Bally shirt

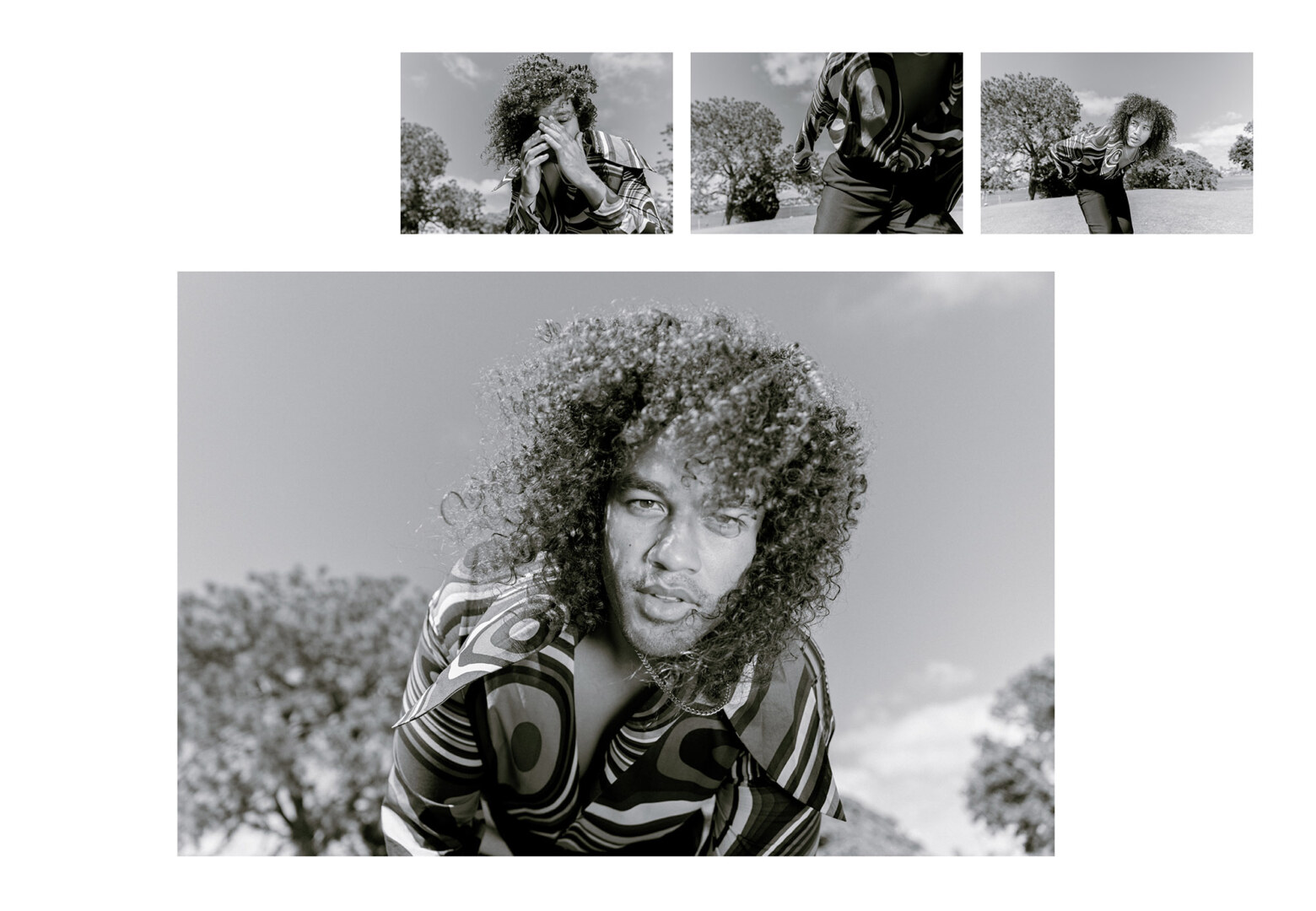

STAND FOR SOMETHING – ZIGGY RAMO BY VANESSA SWEDÉRUS, RHYS RIPPER AND GRACE O’NEILL

TALENT: Ziggy Ramo

PHOTOGRAPHER: Vanessa Swederus

CREATIVE DIRECTOR & STYLIST: Rhys Ripper

GROOMER: Afton Radojicic @ DLM

PHOTOGRAPHY ASSISTANT: Orson Heidrich

INTERVIEW: Grace O'Neill

The magnanimous rapper Ziggy Ramo recorded his year-defining album, Black Thoughts, in 2015 — but he held on to it for five years, told by the music industry that an Australian public so in denial about their own racist past (and present) couldn’t handle its contents. On May 25th, as a global race reckoning began to take shape, he uploaded the album in full —it’s gone on to be dubbed the most important Australian album of 2020. The 16-track record covers everything from our nation’s rarely discussed slave trade to the mainstream media’s deplorable treatment of Adam Goodes. Shot for SIDE-NOTE by his girlfriend, Vanessa Swedérus, Ramo speaks openly about the long road to reconciliation that his home country has barely begun to embark on.

GO: I wanted to start by talking about your childhood. Your family moved around a lot.

ZR: I was born in Bellingen, and we lived in that area in Bowraville for a matter of months, and then moved up to East Arnhem Land and Gunbalanya. We were there until I was six, and then moved to Perth, where I did primary school, and then we moved back to the mid-North Coast again when I was 12, and I did the first three years of high school in Nambucca Heads.

GO: The second half of high school you lived on-campus at Scot’s College, which is an elite, all-boys school in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. I know your parents are both public school educators – why were you interested in going there?

ZR: When I was 12 I started getting this idea in my head that I wanted to move to Sydney – I guess it was my first attempt as showing my autonomy, and I saw it as a kind of mission of personal empowerment. As you said, my parents are both public school educators – my sisters and I always attended public schools – but they were supportive. They basically just said, Well, I hope you figure out a way to pay for it. And so I applied for a bunch of scholarships and ended up at Scot’s.

I inherently understood, even at that young age, that the kind of people that attended these institutions held the language of power in Australia. A lot of those kids either have parents, or will themselves become the kind of people who make decisions on behalf of what’s happening to Indigenous Australians. I wanted to familiarize myself with their world view and lived experience.

GO: Something strange that happens when you meet people from those super elite backgrounds is that you realize that people aren’t ‘bad’ in the simplistic way we like to think of ‘badness’. A lot of the time it’s indifference and ignorance, rather than proactive hatred. Which often feels harder to tackle, because you have to spend so much time convincing people there’s a problem to begin with…

ZR: Right. When you’re in those corporate, elite, very white environments, you’re dealing with people who believe they have good intentions, but intent doesn’t necessarily equate with good results. For me, navigating those spaces can be a really alienating place to be, because I can navigate that space, I’m eloquent; I can articulate myself and communicate in a way that is very white. My dad often talks about this concept of the ‘third space’, when you have two feet in both cultures. It’s not like you end up being in both, you actually end up in neither of them.

Bottega Veneta jacket, Venroy pants, Timberland shoes

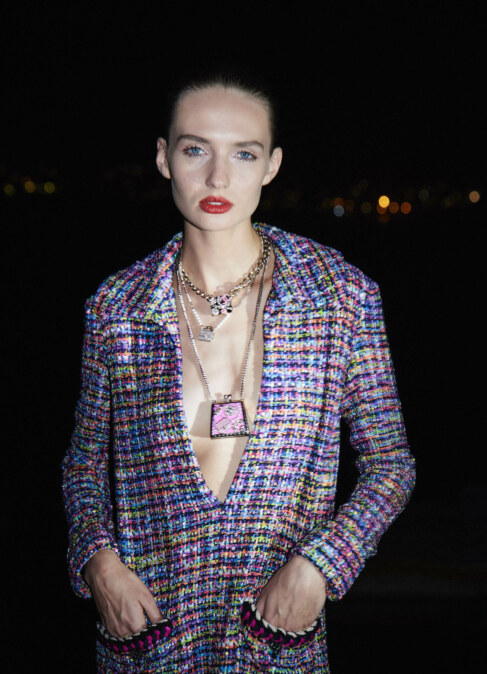

Prada shirt, jacket, pants, shoes & bag

GO: I know you can’t ever compare racism and sexism—and obviously the two intersect in many ways—but I remember when #MeToo happened feeling this flood of contradicting emotions—happy that the conversation is finally happening, but then so angry that it’s taken so long, and at the hypocrisy of so many people. Did you feel that way at all watching the Black Lives Matter protests in May?

It’s interesting you mention #MeToo, because the more you think about this stuff, the more you realize that unless you’re a white, able-bodied, cisgendered, extremely wealthy, heterosexual man, the structures of power in our society are oppressing you in one way or another. It doesn’t work to say, Oh, I’ve been through oppression myself; therefore I can’t be oppressing somebody else. I, as a man, have to be able to recognise the privilege that gives me. If I made super misogynistic music, how could I be taken seriously talking about the oppression of Indigenous Australians? I’d be upholding the exact same structures that I’m trying to dismantle.

People tend to fight oppression when it has real life stakes for them, but then can’t connect to it when it’s broader than that. Which is so dangerous, because then you’re dealing with symptoms and not getting to the root issue. Earlier this year we were all trying to deal with our environment, and now we’re dealing with racial justice, but we need to stop being so laser-focused on ‘me’.

We’re always talking about the same thing when we talk about these issues, which is that all these Western power structures that have just been around in Australia since colonization were designed in a time where women and people of colour were literally seen as objects and not humans. We’re making amendments to that system, but it’s kind of like putting a Band-Aid on a broken leg, then being surprised when you walk around with a limp for the rest of your life.

Hermes shirt, Jessica Crema necklace

Ermenegildo Zegna Couture jacket, Emporio Armani pants, Stum tee, Fendi sneakers, Jessica Crema necklace

GO: I think one of the many things that have been confronting for white people this year was realizing that huge swathes of our own history were hidden from us by our own education system. I read Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor this year, and before that I knew nothing about the British colonization of India. And then in June Scott Morrison got on national television and said that Australia has no history of slavery. And it didn’t seem like he was intentionally lying—I think he genuinely had no idea. In fact, I think most Australians haven’t even heard the term ‘blackbirding’. How did you react to Morrison’s comments? I’m sure you weren’t surprised…

ZR: Not at all. In fact, what shocked me more was that people were surprised by his comments. Of course he doesn’t know. Scott Morrison not knowing his own country’s history is the system working successfully. We were literally treated as a dying race—the government policy was to kill, eradicate and then eventually to assimilate. It’s never been about protecting us, nurturing us, or working in conjunction with us. The Australian government wasn’t designed to govern us, and it hasn’t ever adapted to governing us.

On a personal level, it sucks. Ramo is a Solomon Islander name. My Solomon Islander heritage were enslaved and brought across to work on a sugar cane field. I am literally a symbol of slavery in Australia. You would hope that the leader of your country knows about your history. But if the leader of your country is going through an education system that has never acknowledged or grappled with what we’ve done, and what we continue to do, what can we expect?

GO: Let’s talk about the album. You recorded it in 2015, but were told by the music industry that it would be too difficult to market in Australia. What was the thought process when you decided to release it in June? Did you see a kind of hypocrisy in the way that Australians were reacting to the murder of George Floyd?

ZR: I saw these very intelligent people in Australia doing our typical thing, getting on our high horse and pointing a finger at America. It’s very easy to care about Black bodies that are on the other side of the world, because you don’t have to do anything. You can post on social media, but you won’t actually have to investigate the ways in which you oppress Black bodies in your own country.

No Ordinary pyjamas, Hershan bag, Sawft hat | Commas shirt | Stum sweater, Commas pants, Dior sneakers, Jessica Crema necklace

ZR: Having said that, I’d never before seen us collectively, as a country, be so vocal about how wrong racism is. You only have to go back to 2015, when we as a nation were telling Adam Goodes that he was a ‘sook’ for acknowledging that racism exists. That’s the same mentality that allows the police to be killing us in custody at such high rates, but people just don’t seem to want to join those dots. When I released the album in June, it kind of felt like I was playing to a full house for the first time. The unfortunate thing is, whether you listened to the album when I made it five years ago, or if you listened to it five years from now, it’s still going to be relevant, because the suppression we’re talking about is so deep-rooted that it’s not going to be fixed overnight.

GO: Is it difficult to be on the press circuit, constantly talking about an album that was so emotionally draining to make?

ZR: In a very serendipitous way, having that five-year gap was crucial for me to have a safe distance between now, and the place I was in when I wrote the album. This album is so filled with trauma, and so whenever I performed it, or whenever I’m talking about it, it is re-traumatizing.

When I talk about this actively killing my community, I’m experiencing that first hand, and that puts you in a very fragile space—it’s exhausting. There are a lot of nights where I get really tired, and when I’m overtired I find it hard to calm my anxieties. I’m constantly giving everything, because I don’t know how not to.

Having said that, I also think it’s so important for marginalised artists and marginalised people to be afforded the ability to just be people. Like on this shoot I had so much fun. My work gives me purpose, it makes me feel fulfilled—but it isn’t often fun. Working with Rhys [Ripper] was so refreshing because it’s not often that you come into contact with Indigenous people in this field.

Nikke Horrigan shirt, Commas pants, Dior sneakers, hat from The Atlantic Byron Bay

Dior shorts and jacket, DearFriend shirt, Humphrey Law socks, Bally shoes

Rhys understands the emotional labor we have to carry around, and so he wanted this shoot to showcase me as a complete person. He said ‘I mean this in the nicest possible way, but you’re a big goofball, you’re a bit of an idiot,” – and I am. Even being able to wear luxury brands, I personally never really wear luxury brands, and Rhys said to me, “Non-indigenous artists get dressed in these things all the time without having to buy them!” Doing this shoot made me realize how important is to display those multitudes.

GO: We’ve been talking for an hour and a half now! Thank you for your time.

ZR: I have no idea how you’re going to cut this down.

GO: Is there a note you’d like to leave on?

I’m just very conscious of the fact that my oppression has manifested in me making art and being able to talk eloquently about that lived experience. But other people’s manifests into petty crime, alcoholism or substance abuse, or their being very distrusting and not wanting to educate you, or actually being really, really angry. And your responsibility as the oppressor is to be able to dismantle your bias and come from a place of unconditional love. If you can love me when I can look pretty in photos, or when I make art that you respect, even if you find it challenging, you should also be able to practice unconditional love when we, as a community, do things that you don’t understand and you don’t agree with.

Because we’re all grappling with trauma every single day, and when you’re traumatised, sometimes you don’t have the capacity to hold the hand of the person who is actively traumatising you, sometimes you just want to scream Fuck off. It can come at a great cost to do what I do—I’m not always this light-hearted person, because you carry a weight around with you. So I think it’s really about trying to build people’s understanding about humanity, and about learning to love us unconditionally.

–

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.