WRITTEN BY: Grace O'Neill

Even for women who hadn’t bought a magazine in years – and of those, we know, there are many – there was a sense of something ending on Tuesday. In one deft manoeuvre three of the final stalwarts of the Australian fashion magazine landscape were wiped out. Harper’s BAZAAR, ELLE, InStyle. Gone, gone, gone. A strange thing happens when you are too close to the action – it takes you a little longer to grapple with the wider cultural impact of events like these. Yesterday was for friends and colleagues – for tears and soliloquies and wine, for thank yous and sorrys and for reflecting on our cumulative decades of work – good work – work too good to be reduced to a headline. Today, I guess, is for eulogising.

Nobody who worked in magazines was naïve to our industry’s impending demise. We had spent years watching the dominoes fall around us. We watched friends find out their magazines had closed from Mumbrella before the company deigned to inform them. Others were rounded up into ominous 9AM meetings and forced to leave the building that afternoon. CLEO gone. Dolly gone. Cosmopolitan gone. These titles slipped through our fingers so stealthily, so quietly, that we never really had a moment to mourn what it meant that they were gone.

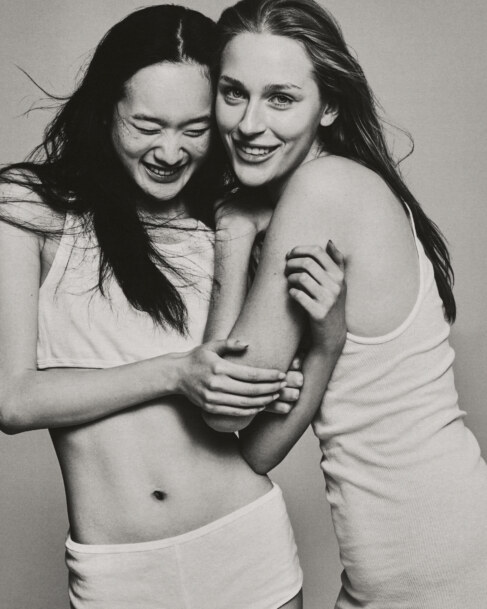

I can’t overstate how skilfully those remaining teams managed unrealistic and untenable expectations with originality, grace, intelligence and humour. The legacy of this particular moment should be the dozens of women and handful of men who walked into work every day knowing the ground beneath their feet could crumble at any moment, but showed up anyway. Many of us did so because we still held on to this romantic notion of what magazines were supposed to be. In a world hell-bent on reminding women that our interests are facile, superficial, unimportant and unintelligent, magazines have always been a safe haven. Every person who works or who has worked in magazines stayed with their boat, even as it sank, because they wanted to keep that magic – a magic that means something different but equally powerful to each of us – alive.

The first issue of ELLE gave me – an ambitious university student with a questionable sense of style and a voracious appetite for the world – a blueprint of the kind of woman I could become. Intelligent, well-travelled, well-read and well-dressed – who listened to Banks and FKA Twigs, who wore Topshop dresses with expensive shoes, who loved Girls but could fairly critique Lena Dunham in a wine-fuelled discussion, who had been to Prague and Delhi and San Francisco, who understood that style was not a substitute for substance. A future version of myself came into startling focus when I read those pages.

I remember the giddy sensation of seeing my name written in those pages for the first time – the feeling that you’ve joined a legacy. There, in black and white ink, is a reminder, in a world of increasing impermanence, that some things are permanent. Things will change and your life will take unexpected directions but there will always be, stored away in a box in your mother-in-law’s house, that magazine, with your name on its pages. I began at ELLE as an intern and over the next seven years worked as a writer, then an editor, then a director, across ELLE, Harper’s BAZAAR and briefly, Cosmopolitan. The privilege of being the gatekeeper of our safe haven was great, but the job became harder and harder.

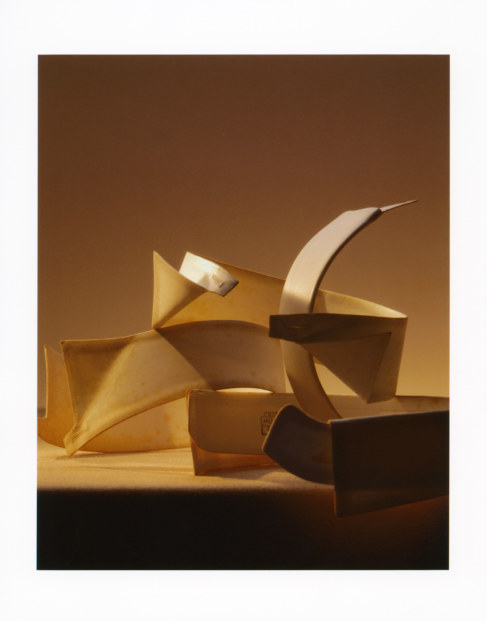

Skilled, intelligent, thoughtful editors were given a fraction of what was needed to produce the magazine they spent decades dreaming of creating. Directors could no longer commission the country’s most talented writers; despite knowing these were the commissions that paid their rent. Instead we wrote everything ourselves, creating a homogeny of (mostly white) voices at a moment where we knew that homogeny would be our death knell. Restrictions on shoots meant realism began to replace imagination in an industry that can only exist where the opposite is true. The country’s most skilled photographers created beautiful imagery while only just breaking even on their shoots. Branded content became the norm, and the desire to create engaging, original, thought-provoking stories with ever-smaller teams and minimal resources was the source of daily – hourly – exhaustion.

Creativity and commerce are always butting heads, but in the last five years that fight has progressed to an all-out war. The essence of magazines – especially fashion magazines – has always relied on a breadth of vision and that vision costs money. The ever-present lack of funds loomed over every meeting, every editorial decision, every shoot. To compensate, we began to romanticise the link between austerity and creativity – I now think this may have been a mistake. Yes, our country’s most renowned creatives have consistently risen to the challenge of creating beautiful imagery and thoughtful words on a small budget. But to be constantly underpaid for your work – to be the best in the entire country at what you do and yet rarely be fairly compensated for it; to be consistently asked to work for free or for discounted rates; to be told you should just be grateful to have a job, even when you are underpaid and overworked – that becomes a kind of systemic gaslighting. I’m not sure that the blame for that lies with any person in particular – but it’s because of this, I think, that yesterday’s news was a heavy sadness tainted by a quiet and unsettling flicker of relief.

Call it naivety, but I hold out hope that this is a pause and not the end of the story. I believe our generation will come to re-appreciate the permanence and tactility that print media offers, that we will grow to understand the importance of paying for content, that we will find that digital content doesn’t fully satisfy us. But when that happens it’s the industry’s job to be ready. To be agile, dynamic and innovative. To abandon the shackles of rigidity and tradition and to transform the entire definition of what the word ‘magazine’ can mean.

As for right now, we need to remember that ELLE, Harper’s BAZAAR, InStyle and the many other titles that have been closed were simply amalgamations of talented individuals. Those individuals may have been splintered apart, but their creativity, talent and ability remains unscathed. They will take a moment to mourn and then they will be back, doing what they do best: creating. And when they do, it is your job, our job, to support them. COVID-19 has reminded us that we cannot rely on large corporations to direct the flow of money to the most deserving places. It has also reminded us that we have, in our own individual ways, the power to do that ourselves. Perhaps the greatest lesson we can learn from the last 24 hours is this: a new media landscape has just been born, and we get to decide to what it looks like.

–

We acknowledge the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional owners and custodians of the land on which this content is published. We pay our respects to Elders past and present.