Bella wears Maggie Marilyn Somewhere singlet | Flash Jewellery chains

INSIDE OUT BY ED TRIGLONE, ISAAC BROWN AND ISABELLE TRUMAN

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Ed Triglone @ The Kitchen

ASSISTANT: Mondo Hays

PHOTOGRAPHER: Isaac Brown

MAKEUP: Nadine Monley @ Saunders & Co

HAIR: Taylor James

STYLIST: Emma Kalfus

CHOREOGRAPHER: Davide do Giovanni

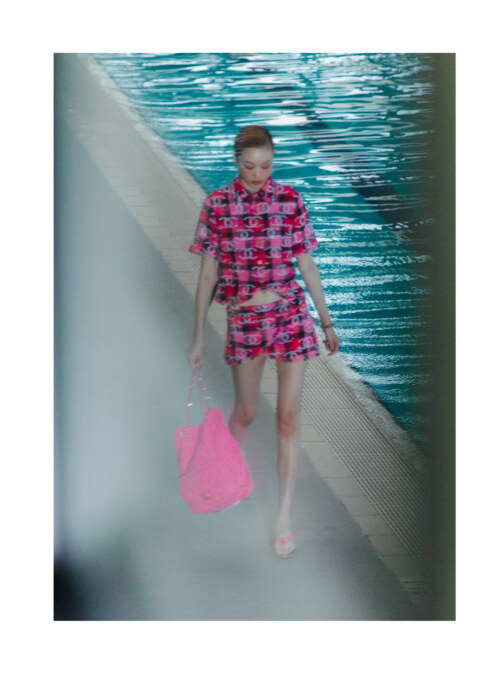

MODEL: Bella Thomas @ Kult

DANCERS: Chloe Leong and Allie Graham

DESIGNER: Ady Neshoda

Special thanks to Paramount Recreation Club

“Now is the time to be brave.” New Zealand label Maggie Marilyn, helmed by founder and designer Maggie Hewitt, posted on Instagram on November 4th accompanied by a one-minute video announcing the brand’s new direction: no stockists, no wholesalers, no sales. “We will design slowly and mindfully, ensuring everything we produce is traceable and organic or repurposed,” the caption read, going on to explain that the seasonal fashion model is created to encourage consumption, with sales prompting consumers to believe that clothing devalues over time. From now on, Hewitt wants to do things differently.

For those who have followed the brand since its inception in 2016, the pivot, while undoubtedly bold, isn’t surprising: Just as much as its name brings to mind whimsical, pastel coloured dresses and images of First Lady Michelle Obama standing on stage in a mint green two-piece suit, so too does the concept of sustainability: Since its very beginning, Maggie Marilyn has championed the earth, long before it was on trend to do so. But even so, cutting ties with the biggest retailers in the world – Net-A-Porter, Neiman Marcus, Selfridges, FarFetch… the list goes on – can’t have been an easy thing to do for a small business at the end of the world in the middle of a global pandemic and subsequent economic recession. So why now?

“I felt like the pace at which we were moving was unsustainable in the true essence of the word,” Hewitt tells me over Zoom from her studio in Auckland. “I just felt over it. I wasn’t enjoying designing and, to be honest, I’d gotten to the point where I really didn’t know if I wanted to be in this industry anymore.” To hear Hewitt sound so pessimistic is unusual. Anyone who’s spent more than a few minutes in her company can attest that both personally and professionally, she’s usually infectiously positive.

Growing up in the Bay of Islands, a beautiful rural part of New Zealand’s east coast, Hewitt was surrounded by nature and animals. But it wasn’t until she started studying at Auckland’s Whitecliffe College of Arts and Design, learning exactly how clothes are made and the impact that the production chain has on the environment, that her passion for sustainability was born. Though the New Zealand fashion industry is small – and we both lived in the same city for much of our twenties – I didn’t cross paths with Hewitt until someone in her team reached out to me on Instagram last year. They wrote that she had noticed the articles I’d been writing about climate change and said that she wanted to gift me a piece from her collection as her way of thanking me for continuing to champion the planet. A friendship was born out of a shared passion and, equally, a shared disdain for the way the fashion industry works. Moreover, how reluctant it seems to be to want to implement lasting change. This disdain was what ultimately prompted Hewitt to make the biggest decision of her career to date, cutting off a key area of her business – and a significant portion of her revenue – to stay true to her values.

Bella wears Maggie Marilyn Somewhere singlet | Flash Jewellery chains | Esant trousers

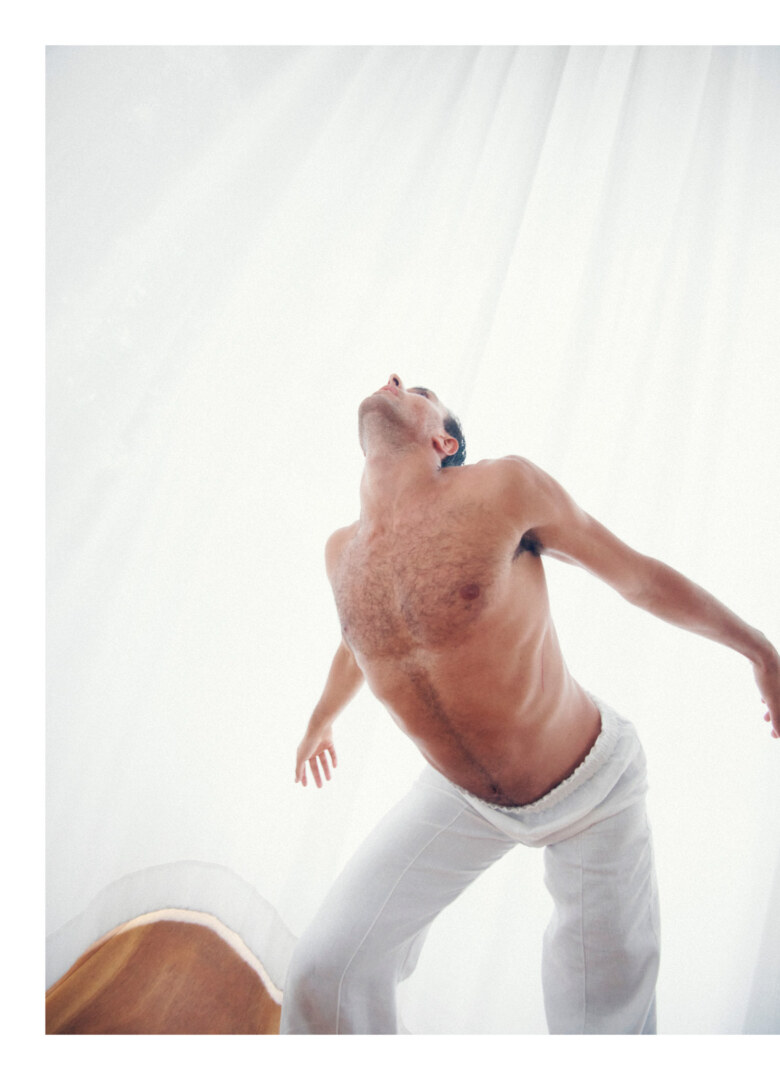

Davide wears Maggie Marilyn Somewhere pants

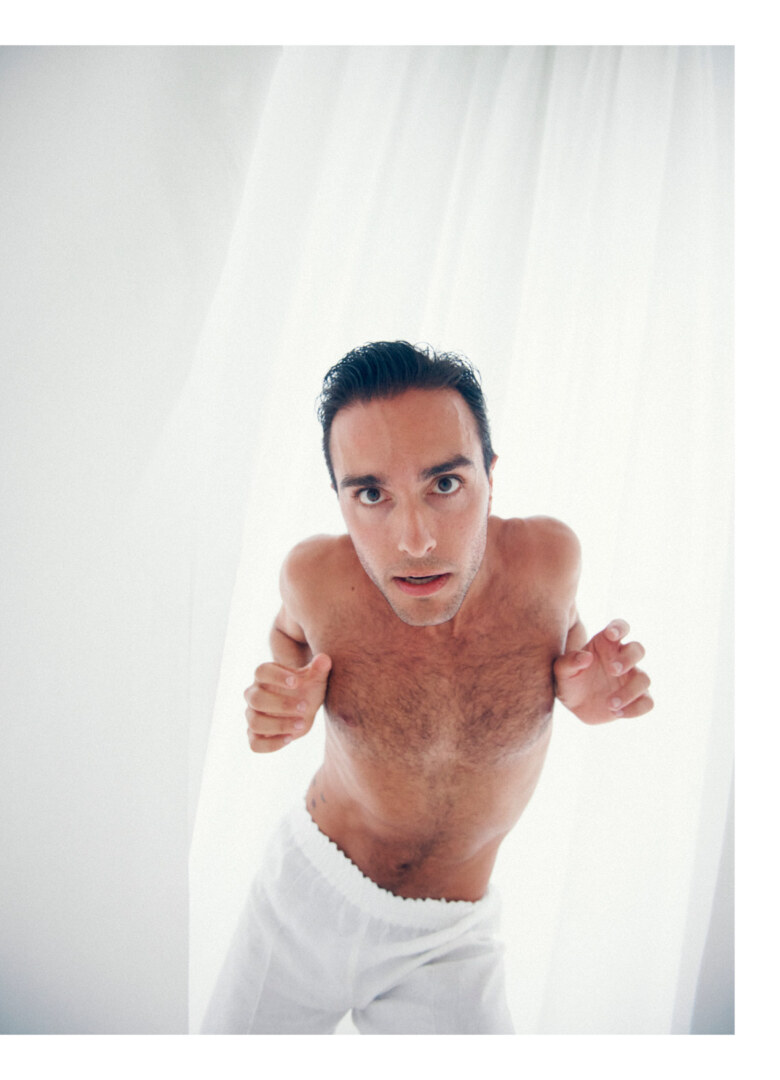

Davide wears Maggie Marilyn Somewhere pants

Within two years of graduating in 2015, Hewitt was selling her designs through more than 70 international stockists. The incredible pace at which her company grew meant that though he was making waves in the industry both locally and internationally, she found it hard to keep track of both her consumer and her brand mission. “I think we got stuck on this hamster wheel,” she explains. “I got into this industry because I wanted to make a difference. But it was almost like I had to play the game in order to be able to attempt to change it. Once I really understood the mechanics of how it all worked, I was like, ‘Wow, this is really corrupt and really not right.’” Hewitt’s referring to the optics brands and stores would project, vs what was really a priority behind the scenes. She found that though retailers were drawn to her message, a lot of the time it was their solution to ticking the sustainability box, rather than the makings of a partnership born out of a shared belief of creating a better future. “I got to my fifth season in Paris selling the collection and I felt like I was just screaming inside a glass box,” she says. “I felt so much frustration realising that the wholesalers I was speaking to still really didn’t give a shit. I wanted to know what we could be doing to amplify our mission and how we were going to educate consumers, but in return I had one of the biggest stores in the world say, ‘This just isn’t important to us right now.’ This isn’t important to you? What do you mean? We’re literally in a climate emergency.”

Hewitt is now working to realign and reverse her inventory ratio from 80 per cent seasonal collections and 20 per cent Somewhere, to 95 per cent Somewhere and five per cent Forever capsules – small seasonless collections that she’ll release whenever she thinks her consumer is missing something – opting out of the seasonal trend cycle and constant production and showing her customers that clothing doesn’t – and shouldn’t – devalue over time. It’s a brave move for someone who’s revenue has been wholesale-based since inception, but Hewitt stands by it: “Fashion is inherently supposed to be such an innovative industry. It’s a creative industry, but the way it operates as a business model is just so unprogressive ,” she muses. “We’ve been doing things the same way for the past 100 years. Business and entrepreneurship in its truest form has always been about questioning things, disrupting and trying to find a better way of doing things.”

A deciding factor in Hewitt’s decision to go completely direct-to-consumer and seasonless was the success of Somewhere, a circular, traceable, range of evergreen essentials with a more accessible price point than the main line and an extended size offering. Hewitt launched Somewhere in 2019 while she was still trying to figure out how to get off the hamster wheel she’d found herself on and says that at the time the collection “felt like a little ray of sunshine” in amongst it all. What’s even better is that Hewitt’s small utopia resonated with consumers: since its launch, the company has seen a 140 per cent revenue increase and 90 per cent web traffic increase each quarter alongside a 95 per cent increase in conversion rates year on year. Somewhere has now become Maggie Marilyn’s “bread and butter,” proving Hewitt’s vision is one that’s resonating.

Somewhere’s success has proven that as we, as consumers, become more and more educated about the world around us, and the conversations about capitalism and consumption become more mainstream, we are no longer satisfied by simply reading a ‘sustainable’ tag thrown onto garments. We want to shop consciously. We want to know who made our clothes, where they were made, using what materials and where from. We want to know where our money is going, who it’s going to and whether companies’ values internally match the message that they’re externally projecting. This heightened engagement has seen many brands fold this year, after the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement spotlit companies who were promoting on billboards a message vastly different to that of what they were saying in the boardroom. A similar shift is happening slowly but surely in the sustainability space, and Hewitt, who found the disconnect between the industry and consumers a huge issue, is one of the few designers not only welcoming but actively encouraging these hard hitting questions. “I realised I can’t be a part of this broken system where we’re not educating the customer,” she says. “We can do all that we like as a brand but really if the customer isn’t being educated, we’re never going to see change.”

Davide wears Maggie Marilyn Somewhere pants

Bella wears Maggie Marilyn Somewhere singlet | Flash Jewellery chains | Esant trousers

Of course, Hewitt knows it’s easy for a small, relatively new brand to point the finger at huge well-established companies, who have a lot more hoops to jump through when it comes to implementing new practises. “I’m not naive to the fact that these big department stores can’t just turn the ship around overnight,” she says. “But for me, integrity is a really important word. With a lot of our retailers, it really felt like there wasn’t an intent to do the right thing. I think if I could have seen that there was, maybe there could have been a way to salvage some of the relationships, but for the likes of a lot of our big department stores, it really was just about selling a story to get more customers in the door, as opposed to actually believing in that story,” she explains. “There was a lack of integrity and we just couldn’t do it anymore. That’s against everything we stand for – we don’t just sell the story of using fashion to create a better world, we really want to make the world a better place.”

All things sustainability aside, it’s just smart business to implement practices that are good for both the planet and the people living on it. Not just because it’s the right thing to do, and consumers are now taking more notice than ever before, but because governments are not going to be able to ignore the climate crisis for much longer. “It’s actually the only thing to do if you want to be here in 10, 20, 30 years time,” Hewitt, who sees the likes of carbon taxes and fees for importing non-organic cotton in our near future, says. “I do think that soon there’ll be a carbon tax and you’ll have to pay to pollute. I just think you’re setting yourself up for the future if you are already implementing these things into how your business operates and it’s part of your margin.”

When we touch on the year that’s been, and how the climate emergency has taken a backseat to the pandemic, US election and race reckoning, Hewitt and I begin to speak about how issues can seem too large and terrifying to tackle when you look at them too broadly. People can become paralysed with the sheer immensity of what needs to be done and, instead of facing the issues, often end up looking away. But when you bring it down to what you can do, as an individual – whether that’s shopping at your local farmer’s market instead of supermarket, buying from local-owned businesses and supporting companies who share your values, you really can make a difference. “Sometimes fashion seems like a frivolous place to start,” Hewitt says. “But really, fashion is such a conduit for so many different industries – everyone buys clothes, so everyone partakes in fashion in some way. If we can be a big enough player in fashion, hopefully we can inspire other industries to be more circular in how they operate…. and then you really can change the world.”

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.

Bella wears Maggie Marilyn Somewhere singlet | Flash Jewellery chains