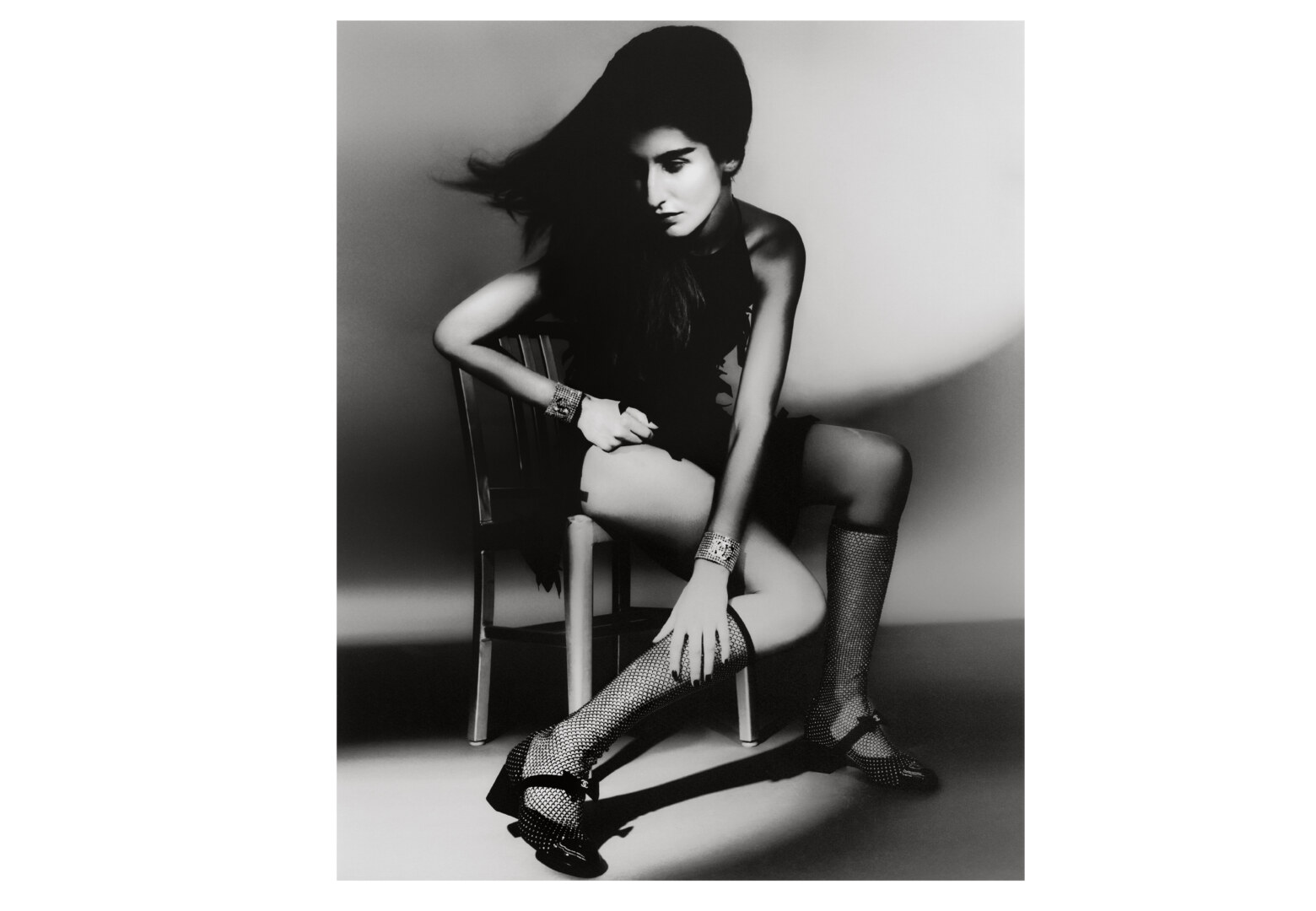

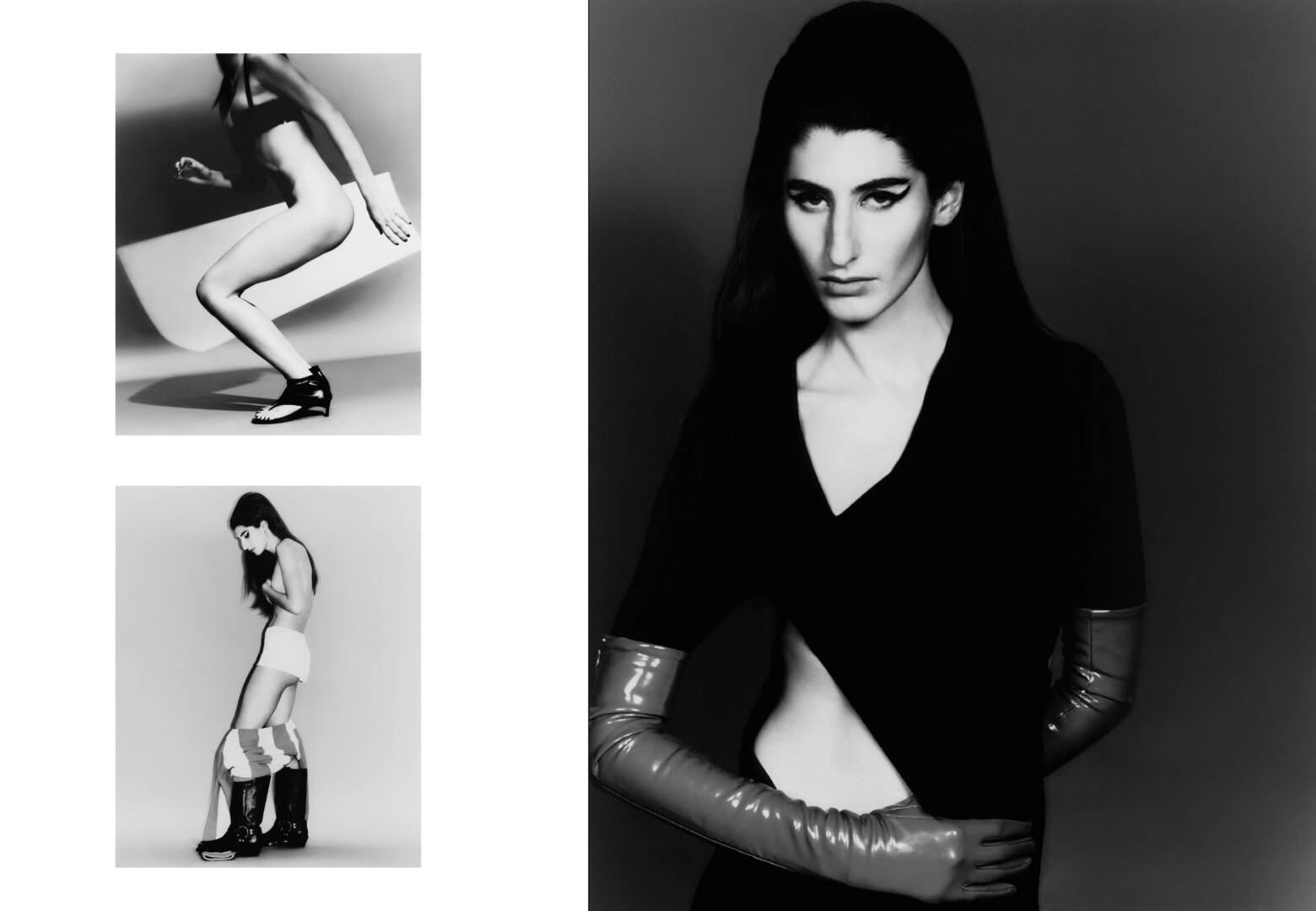

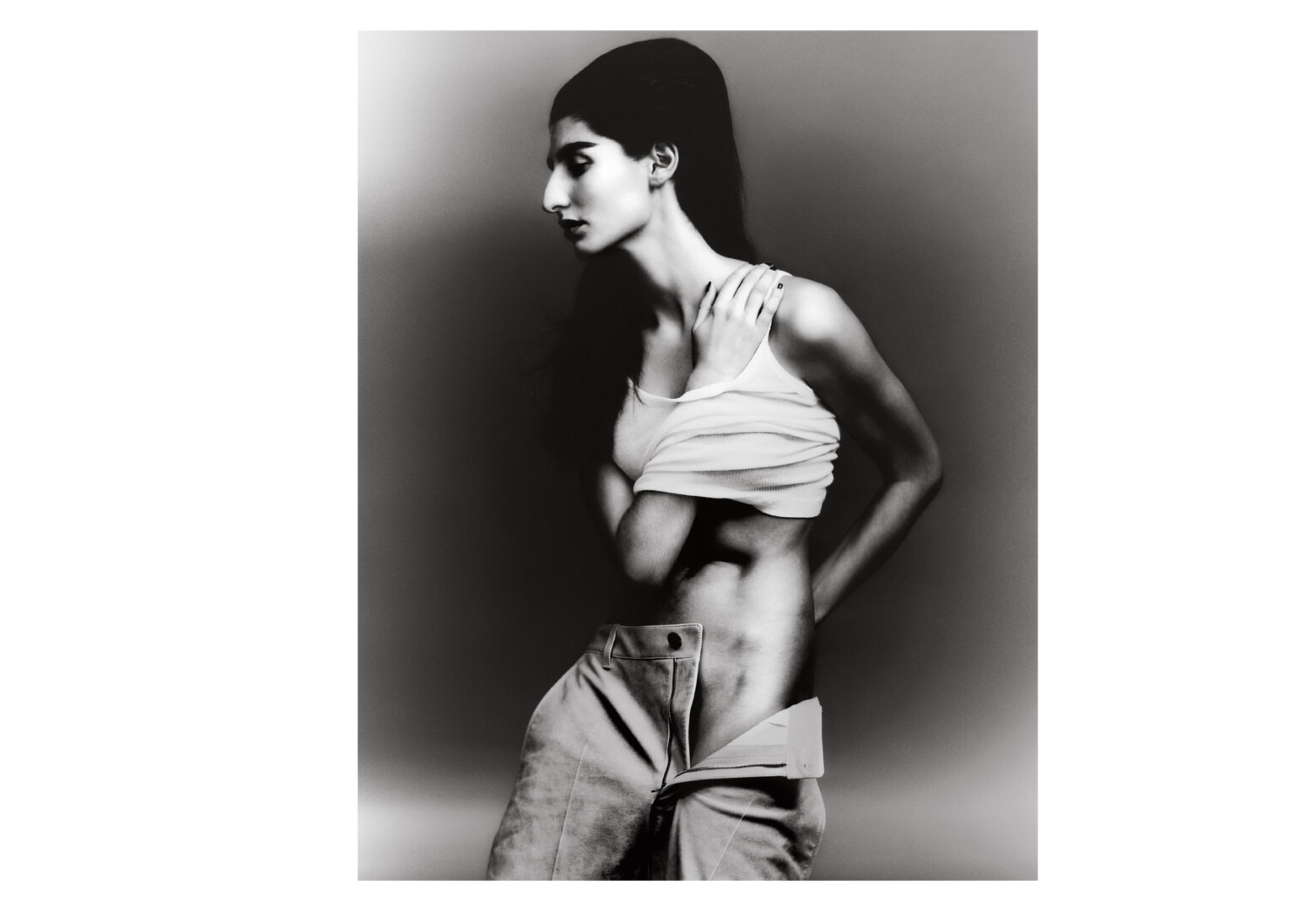

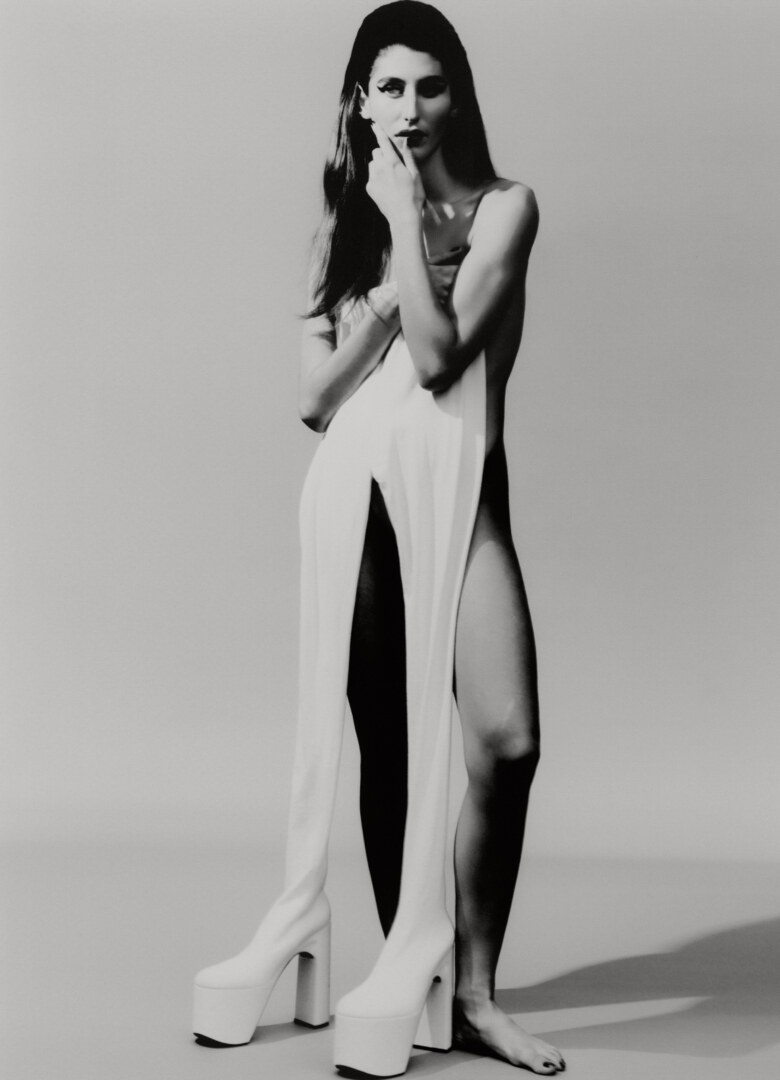

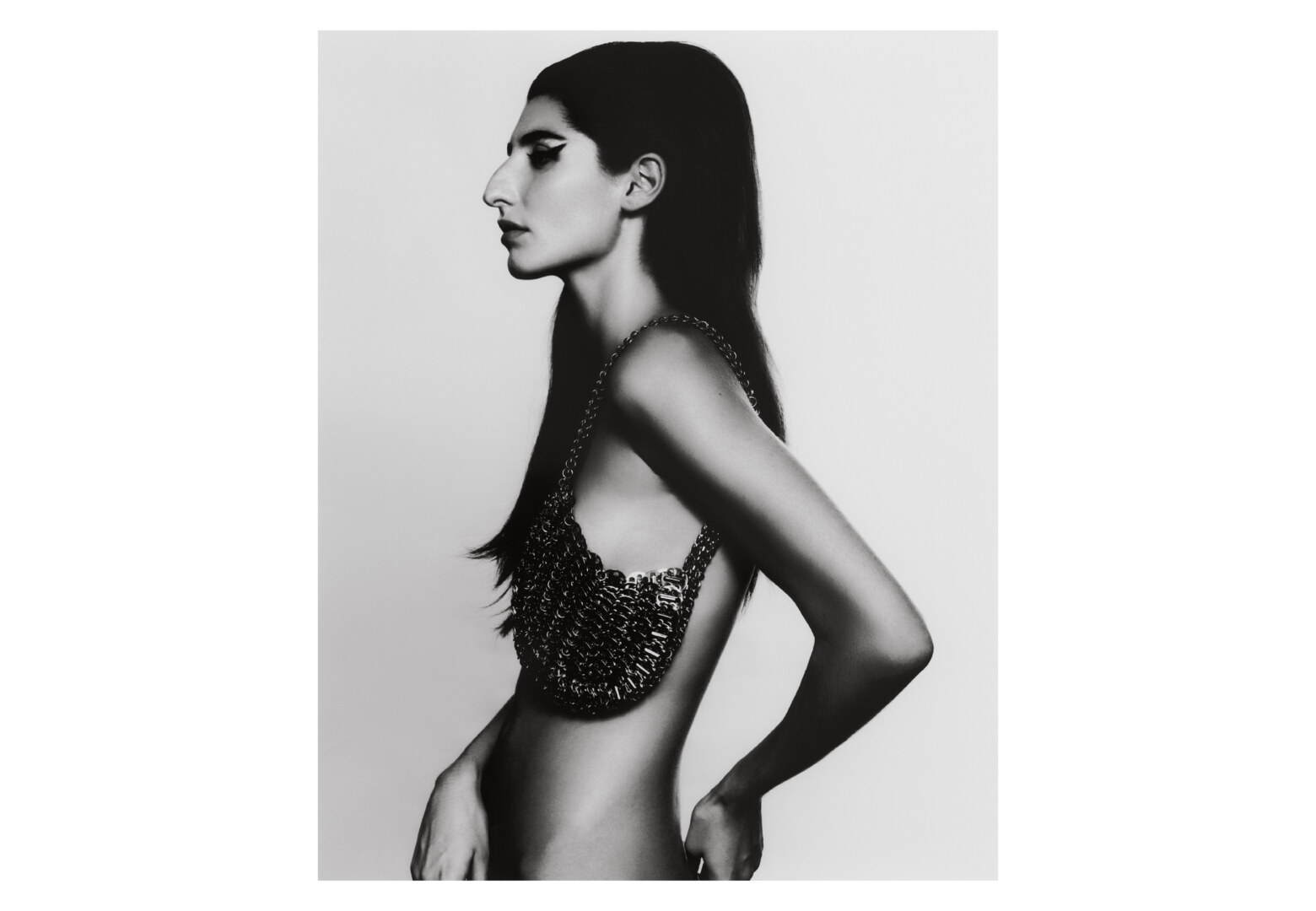

EVERYTHING LEFT UNSAID BY LEVON BAIRD AND MARIELA SUMMERHAYS

PHOTOGRAPHER: Levon Baird

STYLIST: Freddie Fredericks

HAIR: Sophie Roberts

MAKEUP: Linda Jeffreys

MODEL: Frany Richardson

WORDS: Mariela Summerhays

DESIGNER: Francesca Nwokeocha

“The idea of censorship is thousands of years old,” psychotherapist Mitchell Smolkin starts. Smolkin’s work largely focuses on the dignity of suffering, and I’ve asked him if he could conceive of a reason why one might self-censor themselves. He begins with contemplation of philosophy.“Self deception was discussed by Plato, and used as a metaphor for the burgeoning consciousness of the human being. In Plato’s cave, he posited that the freedom that comes with self-expression is highly threatening to those that are unaware, and therefore censoring oneself can relieve one of a confrontation with the world.” Prisoners in a cave, staring at dancing shadows cast on a wall in front of them, believed them to truly be the objects of which they are only shadows of. That is, until one dared turn around and saw the sunlight stream in from the cave opening, coming to know what the others did not.

From philosophy to psychology and neuroscience, the purpose of censorship has been considered by humans throughout the ages. “The most famous thinker on this idea was Freud; one might argue his entire oeuvre was a meditation on a human being choosing to censor themselves,” Smolkin continues. “The idea of psychoanalysis started with free association, where the doctor tells the patient to just say what comes to their mind and to not censor themselves. Ultimately, it wasn’t believed that this was possible; rather, that human beings, because we are a hybrid of animal and human, are constantly censoring ourselves.” He gives the example of feeling a strong sexual attraction for someone you’ve encountered on the street; we know it isn’t prudent or civil to simply express our unbridled desire for them, “we censor ourselves to main civility, which is crucial to be able to function in society.”

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex — the area responsible for modulating how we perceive a particular behaviour in ourselves, an emotional centre — is constantly making decisions about what is right and wrong. “Without it, when it is damaged, life is disastrous as one says whatever comes to their mind and acts in a completely uncivilised way.” As much as our instinct may be to believe otherwise, self-censorship can aid us in the pursuit of a peaceful and unencumbered life.

It is here, though, in the contemplation of imposed censorship, that the outcomes differ, and become most detrimental to our health. “History has shown us that imposed censorship can actually be quite successful, if not highly nefarious and cruel, with whole societies brainwashed to discard their personal feelings in the service of a controlling government,” Smolkin asserts. Marx was famously quoted as calling religion the ‘opiate of the masses’ after all, he points out.“In some ways, people can actually gravitate or long for someone to tell them how to think and behave in order to reduce their anxiety.”

Balenciaga boots

Paco Rabanne bag

Sportmax shoes

“On the other hand, the most famous example we have of the potential consequences of imposed censorship is George Orwell’s 1984, where we see the individual who comes to consciousness of their difference, and suffers quite a lot in trying to expose the lie.” There are, of course, modern day examples, 1984 no longer a fictional novel, but a metaphor for current and real circumstances. At the time of writing, the United States is contemplating the banning of TikTok, perhaps for reasons other than censorship; but it is impossible to ignore that 150 million Americans use the social platform. Even darker, Smolkin points out, “For instance, Alexei Navalny, who is suffering tremendously in a gulag in Russia for being the most prominent critic of the regime. In the cases where an individual is conscious of being censored, it can have life threatening consequences to their health and spirit.”

So when we fight against that human side of us that self-censors, and allow the animal through; when we are conscious of being suppressed, and fight at all costs to be liberated, what do we gain from self-expression? “While the ideal of freedom of self-expression is probably just that, an ideal that is never fully achieved in the binary sense, there is a lot to be said for the capacity in the human being to embody their longings and find a good enough means of expressing who they are.” Like the prisoner in Plato’s cave, who eventually walked out from the self-imposed confinement, knowing the light was to a better world, despite the other prisoners not believing it was so. Like the stranger in the street who knows to express just enough admiration to begin what may be a grand love affair, otherwise never experienced.

Smolkin impresses that it’s important to remember that this can be a cultural phenomena, more prominent in the West than in collective societies; and that truthfully, it is likely that we have many selves, not just the one, unlikely to ever all be expressed to their fullness. “But on a neurophysiological level, when the body and mind are working well together, and the human being can really leverage language and image to self-express, it can be a highly emancipating experience.”

_________

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.