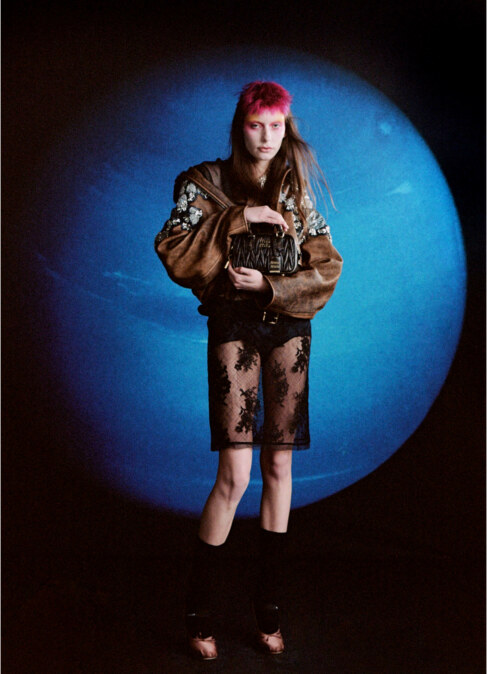

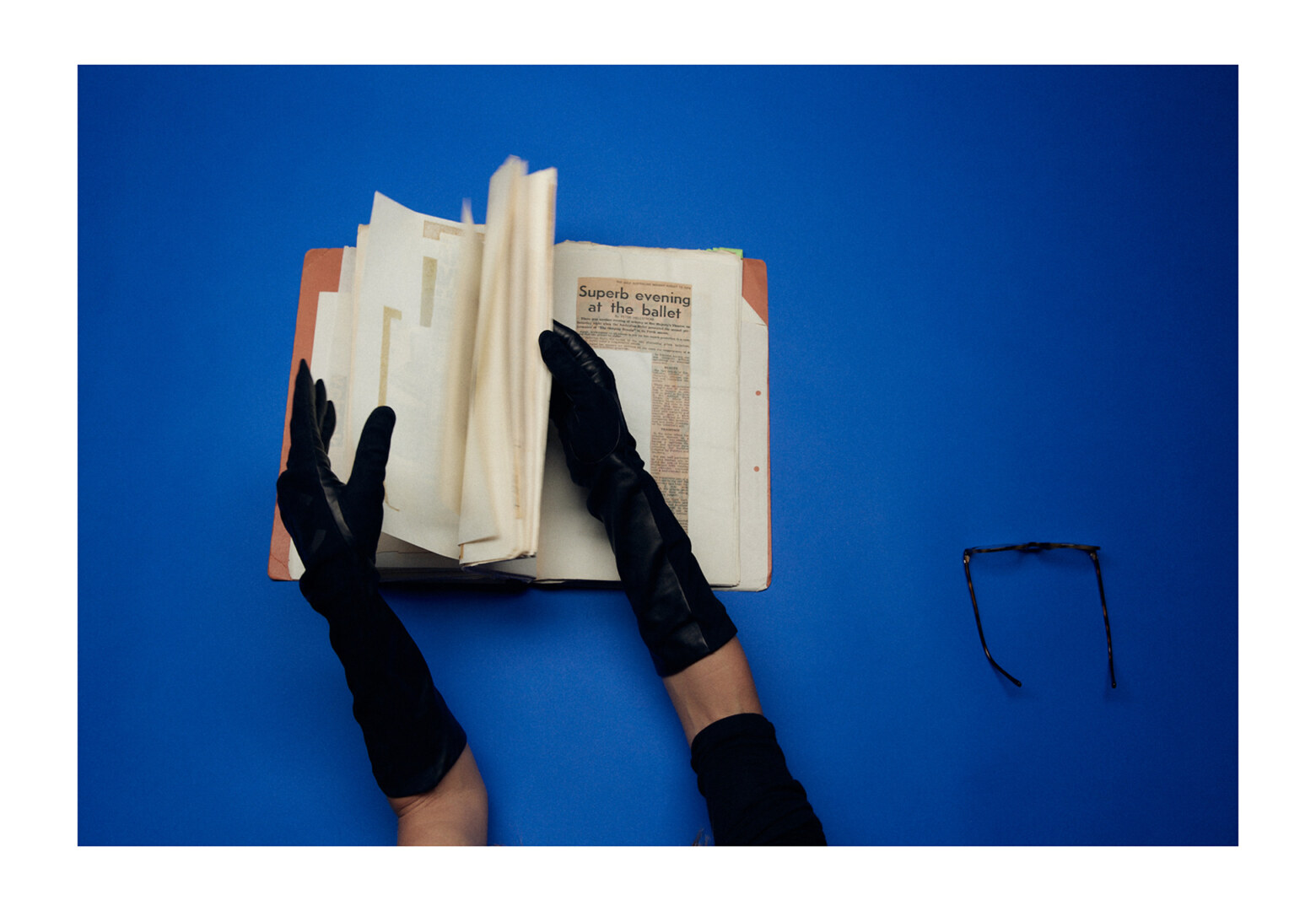

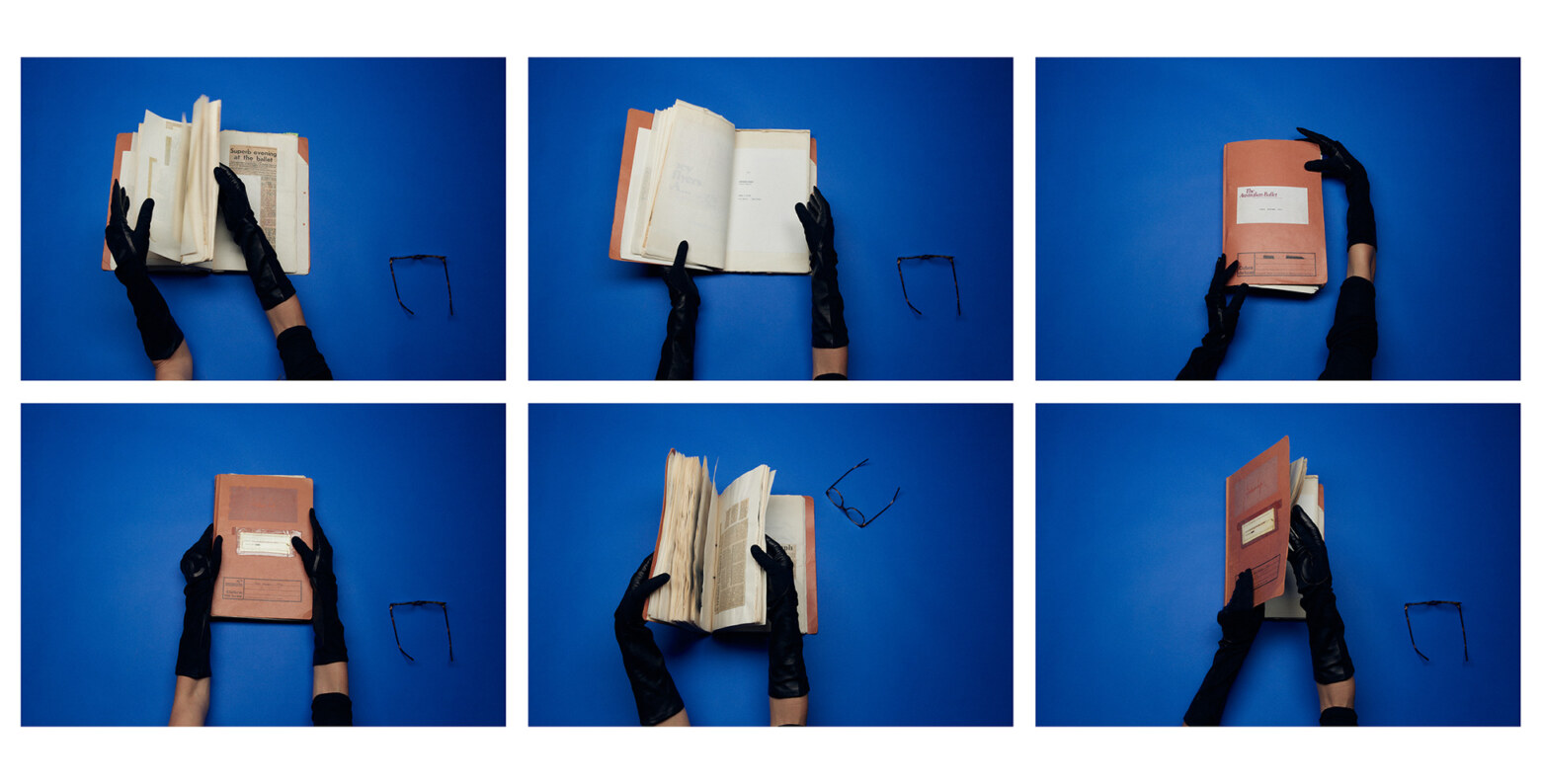

EN ARRIÈRE, EN AVANT- A PROJECT WITH THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET AND CHANEL

PHOTOGRAPHER: Darren McDonald @ The Artist Group

1ST ASSISTANT: Julian Schulz

2ND ASSISTANT: Cameron Cooke

PROP STYLIST: Natalie Turnbull @ Art Box Black

PRODUCERS: Karla Clarke & Emma Kalfus

DESIGNER: Ady Neshoda

Special thanks to Chanel and The Australian Ballet

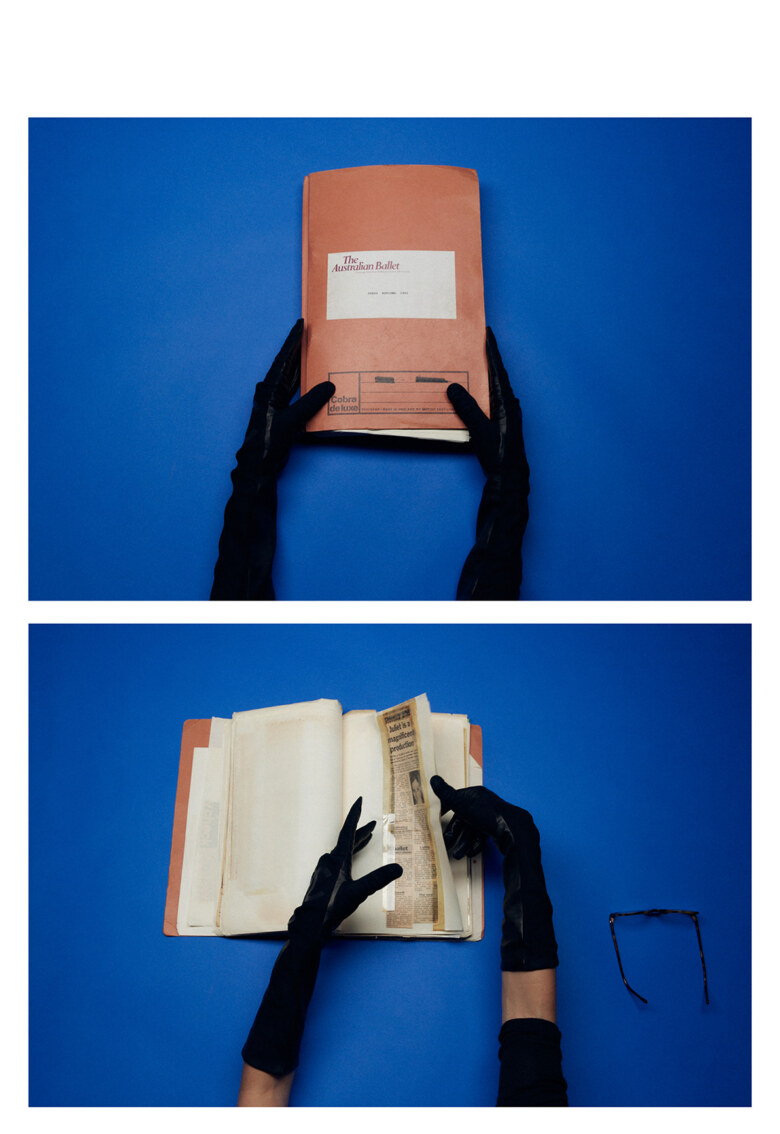

Chanel’s living heritage partnership with The Australian Ballet is a testament to the importance of preserving our nation’s cultural history. The Ballet’s archive is vast and expansive, dating back almost 60 years. “There’s the costume archive, but there’s also an archive of photography, of film, of original publications, basically all the elements that interact with the public,” says Donna Cusack-Muller, The Australian Ballet’s Archive and Records Manager. “We have assets on VHS tape, on film, on cassettes, and previously they just lived in psychical boxes. As the formats evolved, we kept up with that evolution, but we didn’t always have the capacity to access those older formats.”

With the support of Chanel, that vast, 30,000+ piece archive is being digitised and correctly identified, which will include decades worth of footage, photographs, press clippings, and more. All this is happening in preparation of The Australian Ballet’s 60th anniversary in 2022, and serves as a timely reminder of the cultural and social changes the company has witnessed and shaped. Beginning in the ‘70s, when an original production of The Merry Widow put The Australian Ballet on the international map, through the ‘90s, when Graeme Murphy began recreating historic ballets with refreshing touches of Australiana, and up until today, with a new production of Anna Karenina revitalising a cultural landscape which will premiere in 2021—this archive presents a vital part of Australia’s artistic history.

Here, Side-Note takes you through that history, decade by decade, by tracking five of The Australian Ballet’s most memorable original productions.

___

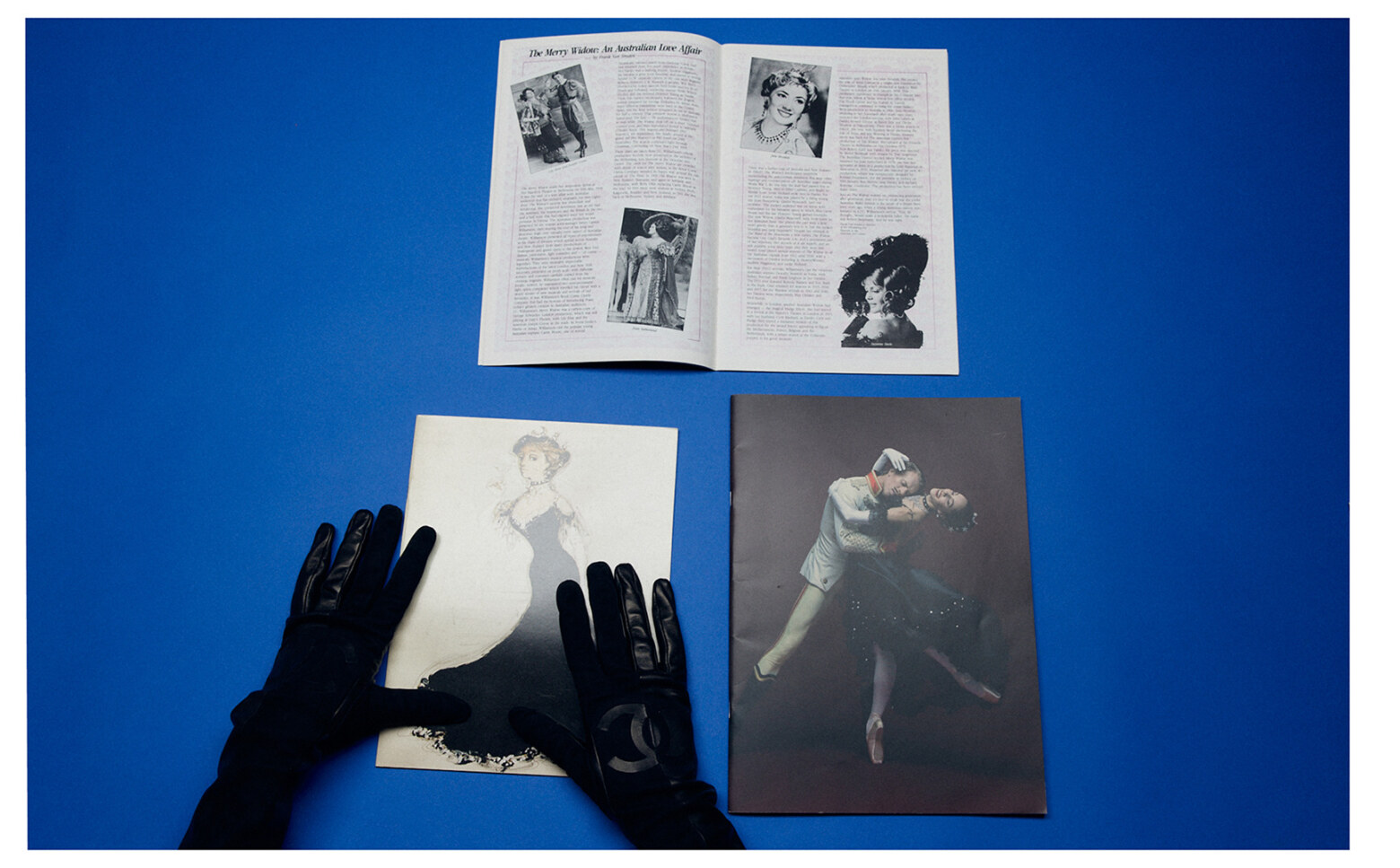

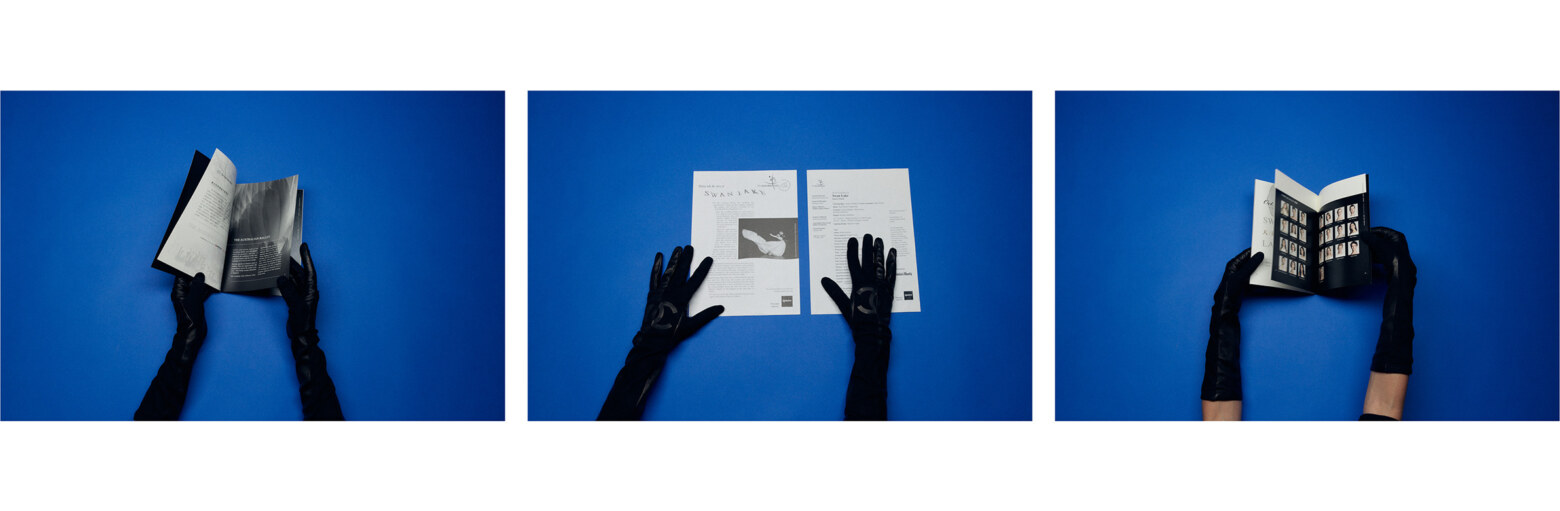

All photographs feature items from The Australian Ballet archive, alongside Chanel gloves and glasses

1970s—The Merry Widow

The Australian Ballet was just over a decade old when it staged its first original production—a make or break moment for any fledgling ballet company. The Merry Widow proved a resolute ‘make’. An adaptation of a long-performed turn-of-the-century operetta, the ballet was crafted by Sir Robert Helpmann, an icon of the stage who was then serving as The Australian Ballet’s Artistic Director.

“To take a story that wasn’t from the traditional ballet canon, and to borrow from opera was a bit of a risk for the company to take on,” says Donna Cusack-Muller. Helpmann was perhaps emboldened by the new cultural climate that was emerging in Australia following the creation of the Australian Council of Arts—the first federal government body to commit to funding the arts—by Harold Holt during the tail-end of the ‘60s. Helpmann called on the choreographer Ronald Hynd and the set and costume designer Desmond Heeley for the production, set in the height of Belle Époque posterity.

“The set and costumes are pure escapism,” says Musette Molyneaux, The Australian Ballet’s Head of Costume Workshop. Perhaps no dresses are more memorable than the white feathered gown worn by Hanna, the opera’s eponymous widow (and modelled here by Amber Scott) in the ballet’s final scene. The gown has had minor restorations, but remains the same garment first worn by Marilyn Rowe, and later by Dame Margot Fonteyn, during the original productions. “Each time it comes out, we just chip away a little bit at refurbishing it,” says Molyneaux.

1980s—Giselle

There’s a fantastic piece of folkloric legend in The Australian Ballet around Giselle. In 1985, during a regional tour of the show, a fire broke out and destroyed the company’s entire set—everything, but the cross marked ‘Giselle’ from the titular character’s gravestone.

This may or may not have inspired the newly-installed Artistic Director, Maina Gielgud, to devise her own take on Giselle—a part she had danced as a ballerina—the following year. It was one of the 40 original productions she would go on to devise during her 14 years at The Australian Ballet’s helm. “There’s a production every decade that defines the company, and in the ‘80s it was Maina’s new Giselle,” says Cusack. “It’s such an important part of the history and DNA of this institution, and it continues to be performed around the world.”

Even those with only a passing interest in ballet will have fallen for the charms of Giselle, one of the true classics of the ballet canon—it is widely-regarded as the most coveted role for prima ballerinas. The tale of a naive young woman who falls in love with a scoundrel, then dies of a broken heart when he abandons her, the enduring appeal of Giselle is tied inextricably to the costumes. Designed in this rendition by Peter Farmer, the ethereal flowing white tutus speak to the production’s poignant narrative, they are the costumes of Willis—the undead.

1990s—The Nutcracker

In 1992, on the eve of its 30th anniversary, The Australian Ballet commissioned the Sydney Dance Company’s then Artistic Director Graeme Murphy to produce a modernised take on The Nutcracker. Arguably the most famous—and most performed—ballet in the world (“there are as many international productions of The Nutcracker as there are little black dresses,” quips Donna Cusack-Muller, Murphy took the basic tenets of the original Russian story, and transformed it into an Australian masterpiece.

Retold as ‘The Story of Clara’—Murphy’s The Nutcracker is set in suburban Melbourne, as an ageing Bolshoi ballerina remembers her life in the early days of the Second World War. It doubles as a kind of faint re-telling of the early history of The Australian Ballet, replacing the whimsical characters of the original with Clara’s forgotten friends and lost loves.

Murphy’s Nutcracker has layers of its Russian predecessors, but remains quintessentially Australian. The set features washing lines, skipping ropes, and the distant hum of cicadas, and the costumes, crafted by Kristian Fredrikson, mirror the pared-back, neutral-heavy tones of The Australian landscape. “In the usual Nutcracker, the Sugar Plum (pictured here) is sugary sweet, in pink or ice blue,” says Musette Molyneaux. “But in Fredrickson’s creations, they are a nod to Imperial Russia, made with rich golds and burgundys, and finished with this fabulous tiara. This garment alone would have taken many, many weeks to make.”

2000s—Swan Lake

Following the mass success of his modernised Nutcracker, Graeme Murphy was called on again by The Australian Ballet in 2002, this time to craft a modernised version of the enduring classic Swan Lake. In the Tchaikovsky original, a tortured prince, unhappy with his choices for a future bride, falls in love with a ‘swan maiden’—a princess cursed by an evil Baron, who transforms into a swan each night—named Odette.

Murphy’s reimagining shakes off the ballet’s fairytale roots and opts for a rawer interpretation. In this Swan Lake, the prince falls in love with a Countess, but is obliged to marry another woman, and the tortured Countess eventually goes mad, believing herself to be a swan. “This was only a few years after the death of Princess Diana, and so everyone who saw it at the time was comparing it to the Charles, Diana, Camilla love triangle,” says Donna Cusack-Muller.

Among the standout costumes, also designed by Kristian Fredrikson, is the remarkable wedding gown, pictured here. The dress is a kind of work of art in and of itself—The Australian Ballet’s version of the Atonement dress. “This dress just shows what an impact choreography has on ballet costumes, and how intertwined they are,” says Musette Molyneaux. “You wouldn’t even notice this dress if it was on a mannequin or a rack, but when it’s worn and moved in it’s transformed. It actually becomes a part of the choreography. That’s so often the case with ballet costumes—they’re designed to add to the choreography, not to limit it.”

2010s—The Sleeping Beauty

In 2015, David McAllister—then Artistic Director of The Australian Ballet—unveiled his sell-out production of The Sleeping Beauty, an opulent visual feast, with lavish costumes crafted by the Czech-Australian costume designer Gabriela Tylesova.

“It was a new production, so everything—the whole set and every costume—was made new,” says Musette Molyneaux. Crafting garments for a ballet is no mean feat. While traditional stage costumes enhance the storytelling, ballet costume designers are engineering garments that will be worn—and moved in, and sweated in—by elite athletes. Construction trumps aesthetics, but aesthetics remain paramount.

“Day-to-day, we have a core team of 14 or so,” says Molyneaux. “But when you’re looking at a brand new production like Sleeping Beauty, that number triples. Plus you’re working with milliners, and wig-makers, you’re crafting the shoes… it’s an incredible amount of work to create a production of that scale.” All up, the production of Sleeping Beauty (still performed today, including a show-stopping appearance by Misty Copeland in the role of Aurora in 2017), features 300 bespoke costumes, 100 wigs and hats, 130 pairs of wings, and required 5,000 metres of tulle.

2020s—Anna Karenina

Anna Karenina—one of the enduring tragic heroines of literature—will be The Australian Ballet’s muse for the 2021 season, a season unlike any other in its history. The appointment of a new Artistic Director, David Hallberg, this year will see the staging of Anna Karenina after it was put on hold in 2020 due to Covid.

Anna Karenina will debut to Australian audience an original production from the Joffrey Ballet company in Chicago. The modernised take on Tolstoy’s classic Russian novel features choreography by the celebrated choreographer Yuri Possokhov, and costumes crafted by the designer Tom Pye. Hallberg, an American who spent ten years as a principal dancer with the Bolshoi Ballet, calls the production “the total arc of emotion. It’s love, it’s desperation, and it’s tragedy. There’s not just one emotion that the audience will leave the theatre with, it’s like Shakespeare.”

“The costumes are so beautifully crafted,” says Musette Molyneaux. “They capture that immediate period look, and have all the attention to detail of the period’s styling, but they also give the length and lightness that allows you to see the dancer’s intricate footwork. I can’t wait to see it on stage.”

___

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.