DEBAUCHED AND SAVING THE WORLD – THE MUSEUM OF OLD AND NEW ART’S 2024 GALA BY ROB TENNENT AND MIKAELA AITKEN

PHOTOGRAPHER: Rob Tennent

WORDS: Mikaela Aitken

Kirsha Kaechele, dressed in a black silk pantsuit, glides into Deco Lounge, the lobby bar for Hobart’s luxury hotel, The Tasman. She collapses in a heap onto a couch, her glossy blonde hair piles above her head, static against the leather. It’s four hours before the Museum of Old and New Art’s (Mona) 2024 Gala — an event Kaechele is at the centre of organising. It’s also the preview day for the museum’s largest exhibition in years, Namedropping; and the second day of Dark Mofo, the museum’s annual mid-winter festival. There’s a lot on Kaechele’s mind, but perhaps front of mind at this moment is money.

The Mona Gala first happened in 2022, and this year is its second iteration. It’s a fundraising mechanism for Kaechele’s charitable organisation the Material Institute. Under this umbrella of good sits a multitude of programs including 24 Carrot Gardens, a food education program operating in some of the most disadvantaged school districts across Tasmania; and Clay & Art Studio, a community-run pottery studio for young people and families.

There’s also the Beauty Lab, which teaches teenagers chemistry, botany, as well as entrepreneurial and business acumen, all under the guise of developing beauty products. “It’s not just about distributing equal opportunity, it’s about distributing outrageous opportunity,” Kaechele says. For each of her ambitious programs, there’s the clear intent to invest in the lower socioeconomic areas of the state.“We want to prepare this generation, who are currently quite ostracised from the new Tasmanian economy, and give them the opportunity to not just participate, but to lead the future.”

This commitment to positive change is what drives Kaechele’s lofty goal of raising upwards of AU$1 million at the gala. “We want to channel resources from extremely rich people and take all their money,” she says, with a rebellious grin. To achieve this, VIP tickets for the gala were $5,000 a pop, of which $4,500 was a charitable donation. General admission tickets were $400, including a voluntary $100 donation. All tickets sold out, and the waiting list is a hefty scroll.

Randy Polumbo pictured at the Mona Gala in his artwork Grotto, 2017. Commissioned by Mona

A magnificently bloated auction catalogue helps further the fundraising. Prized art possessions up for grabs include Andy Goldsworthy’s helmet and raw sketches, and Tony Oursler’s Mesmer’s Triangle. “I’ve been assaulting our friends, shaking them down,” says Kaechele. “I’ve also shaken down my own life,” including art from her personal collection and exclusive stays at two of her and her husband’s private properties. Let’s not forget Kaechele is, after all, ‘Mrs Mona’. She’s married to David Walsh, the idiosyncratic Tasmanian millionaire, Order of Australia recipient, and founder and funder of Mona. But reducing her to such a title is a disservice to her patronage, expertise and moxie. Kaechele is an artist, curator, climate activist and audacious philanthropist. And for the evening, as she’s cloaked in the glamour of Mona, she’ll be chief hustler.

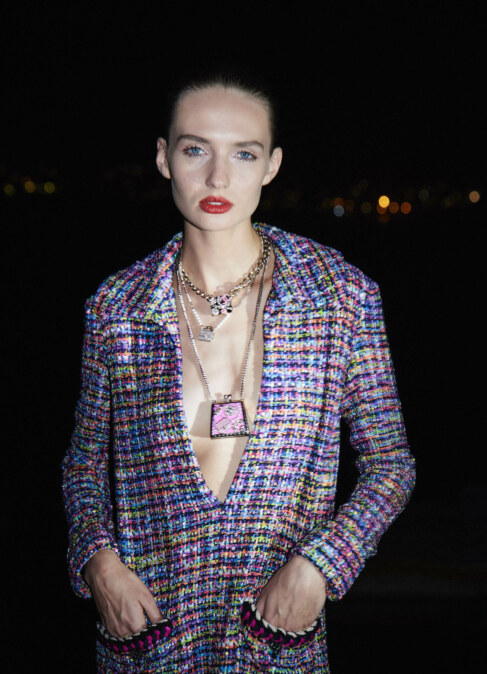

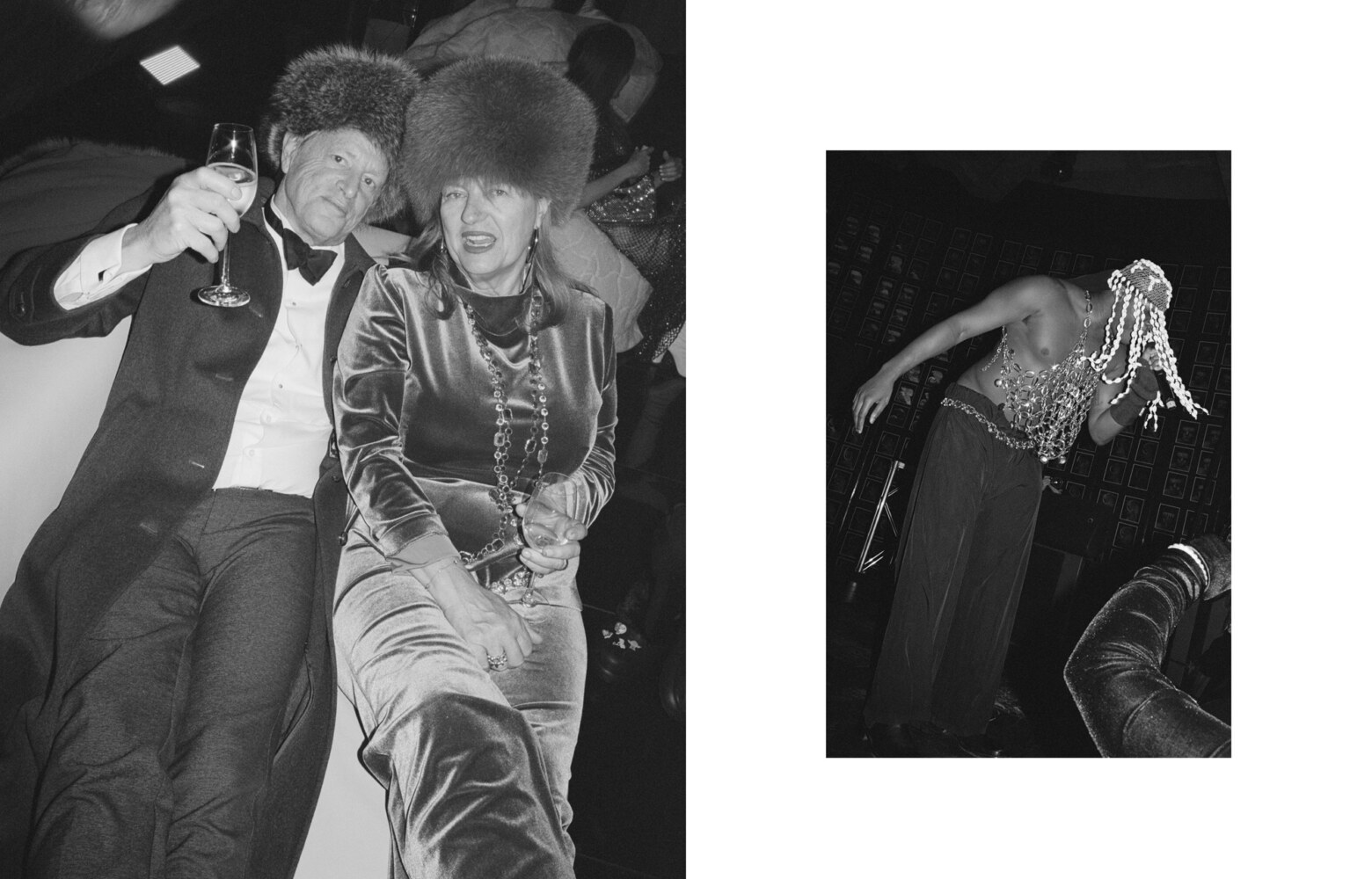

For this reason, no expenses have been spared for the gala. The theme for the evening is class — be it high or low. And the night’s journey begins aboard the Mona Roma ferries, where the champagne is flowing and the waitstaff are suited. Upon arrival at the Mona dock, four motorbikes roar across a tight 20-metre-stretch of pavement, while standing on the stairs is an operatic singer performing in a skintight, leopard print onesie. For the 500-plus guests in attendance, this is only the beginning of the debauchery.

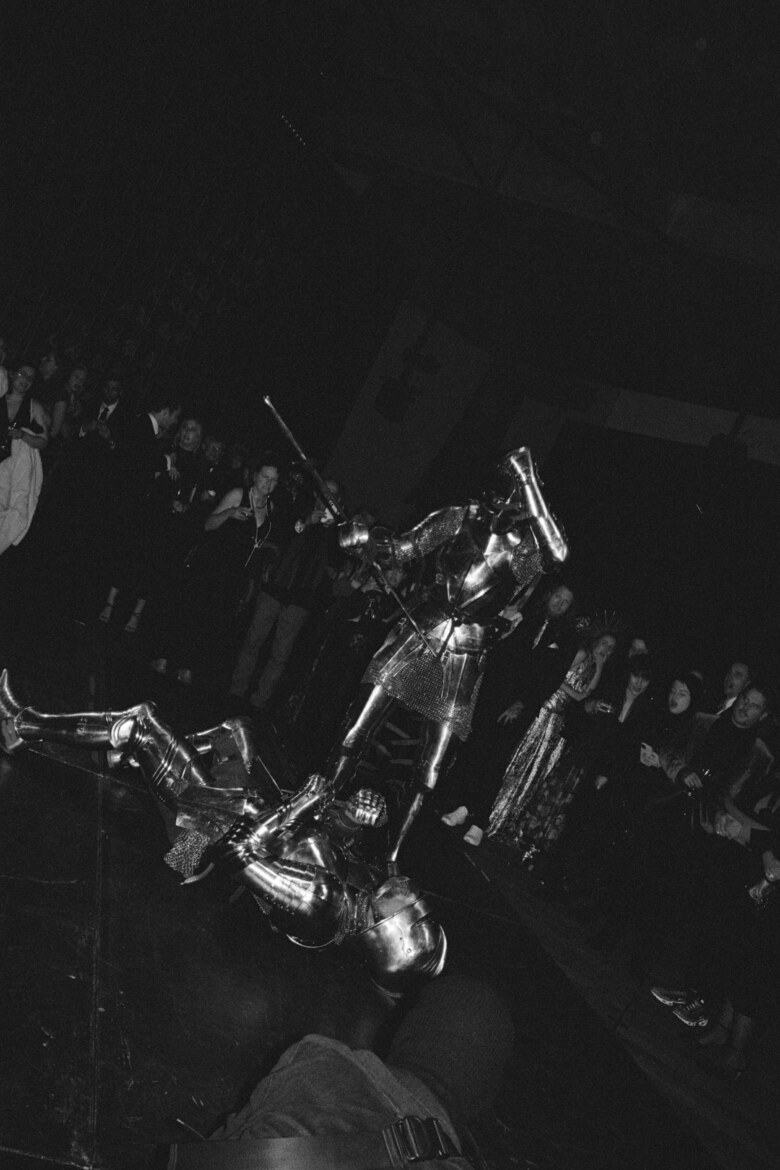

Co-creative directors of Mona’s special events, Willoh Weiland and James Brennan have filled a program with over 80 performers. In true Mona fashion, local mediaevalesque knights, boxers and Irish dancers perform alongside international headliners L’Homme Statue (for their first ever Australian performance). Kaechele has also designed a menu with Mona’s executive chef, Vince Trim. To play on the party’s theme of ‘class’, the team even explored the idea of caviar and Cheezels (an Aussie junk food staple). “But they were gross,” says Weiland, who hints at a grandiose list of possibilities that ended up on the cutting room floor of this ideas factory. “I think that high and low status — what is real and what is not — can be contained in performance, music and food,” Weiland says.

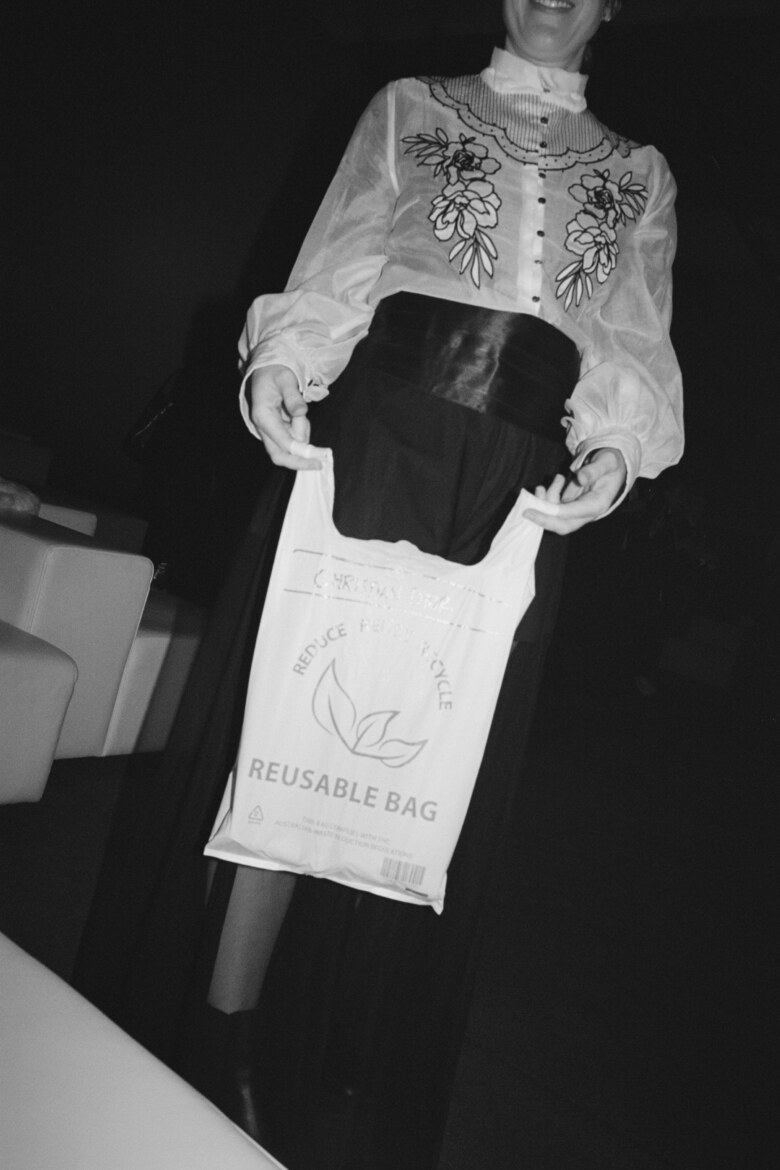

As the guests enter into the hulking sandstone halls of the museum, they’re greeted with a taunt at the Met Gala culture. A Rihanna doppelganger (aka Brazilian social media star Priscila Beatrice) walks the hall, while being papped by frenzied press. It’s a bewildering performance that pokes at a societal obsession with celebrity. It’s also an interesting premise, given the recent backlash at the Met Gala 2024, whereby celebrities were attacked via social media for flaunting their privilege and wealth at a time when war and crisis is so widespread.

Rather than seeing this public sentiment as a barrier for Mona’s Gala, Weiland seizes the moment as an opportunity. “It’s a historical moment that we’re in,” she says, perched at the poker table that forms part of the Namedropping exhibition. “Here we are, at the end of the world, watching the Met Gala. Yet, because Mona isn’t constrained by all of the same fuckery of institutional madness, we’re really able to have the tough conversations.”

In fact, a key part of the Mona Gala is an exclusive walk through of the brand new exhibition, Namedropping. It’s strangely fitting to see a crowd, dressed ironically over-the-top, meander through the rooms clad with objects of status. For the curatorial team, this exhibition has been four years in the making. Perhaps for Walsh, who played a large hand in curating it, it’s more closely aligned with decades worth of questioning. “It’s David putting forward his philosophy on why we make art, and why we namedrop and seek status,” says Kaechele of the exhibition.

It’s the uncomfortable confrontation that we are status-seeking animals. “I like Namedropping, because I think it’s really healthy to give fresh air to these embarrassing truths about humans. It’s sort of therapeutic,” Kaechele says. And for the curatorial team, who in no way claim to be scientists, it is indeed a strong biological hypothesis. “Human beings don’t function well in isolation, we are very social creatures,” says Jane Clark, Mona’s senior research curator who has been with the museum since 2007. “So there’s an obvious show of skills and beauty in order to get a mate. But there’s also the thing of having allies and friends to live with and watch out for you,” Clark says.

The beauty of the exhibition is, your knowledge of art can be blissfully nil. You can gawk at an ancient Egyptian coffin, Beatles signatures, a discredited Van Gogh, a handwritten original of David Bowie’s “Starman” lyrics, or a leather tank of war. Gawking is part of the point. Or you can drink in the visual pleasures of Art Processors’ exhibition design, or raise serious questions about how power, status and identity are dished out, with pieces like Vincent Namatjira’s Vincent and Donald (Indulkana), the Guerrilla Girls’ The Advantages of owning your own art museum and Cornelia Parker’s film Made in Bethlehem. “It’s about showing your face and proving your place,” Clark says.

As the night rolls on, a VIP auction takes place in Faro Bar + Restaurant, where the opening item is a round of caviar for the room. It sells for $1,200, to which the auctioneer, Clementine Blackman (granddaughter of the late, preeminent Australian painter Charles Blackman) shouts, “Caviar for the children!” Six more items are auctioned off, including a diamond bracelet. Kaechele buzzes around the room coaxing buyers. “What Kirsha is doing is openly saying ‘I know these people have money, so come give it to the children’. It’s very transparent,” says Weiland. “We don’t need to be weird about it, and we don’t need to suffer from a lack of transparency.” The auction concludes. Bidders are implored to now turn their wallets to the online silent auction.

Two angelic women, drapped in Gail Sorronda capes, start to circle the room, offering massages to the guests. Topless dancers appear, then following a few songs, disappear. The drinks continue to flow. Meanwhile, outside in the Nolan Gallery, there’s a raucous party bouncing beneath millions of dollars of art. The non-VIP revellers are told to don their black balaclavas. The VIPs then join the room, in bright pink balaclavas. The staff place on their white balaclavas. Class and status is slapped in your face, once again. The tension is diffused by contemporary dance performers Cuddle entering the stage to perform their bizarrely beautiful piece. They flip and fold around each other, disarming wrestling bravado with tenderness and nudity.

As the clock whirs past midnight, then 1am, and onto 2am, the museum floor grows stickier, the ‘black tie with a twist’ outfits groan beneath the weight of the hedonistic party. The music thumps into a transfixed beat. And no doubt, the team is tallying how much was raised for the Material Institute. “In these moments where everything just feels so awful, the nature of pleasure and whether it’s allowed, comes into question,” says Weiland. “One thing I love about Kirsha and David is their clear idea that pleasure does not have to be at stake for you to do good in the world. That feels like such a false dichotomy.”

For the Mona Gala, it’s definitely played out that way. Over $400,000 was raised, and Kaechele and Walsh continue to fund 50% of Material Institute’s programs. So why can’t you do good and have fun while doing it? To this Kaechele puts it very simply: “we can be debauched and save the world”. Mona, debauched? Absolutely. Kaechele and Walsh saving the world? They’re certainly trying to make a dent down in Tasmania.

_________

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.