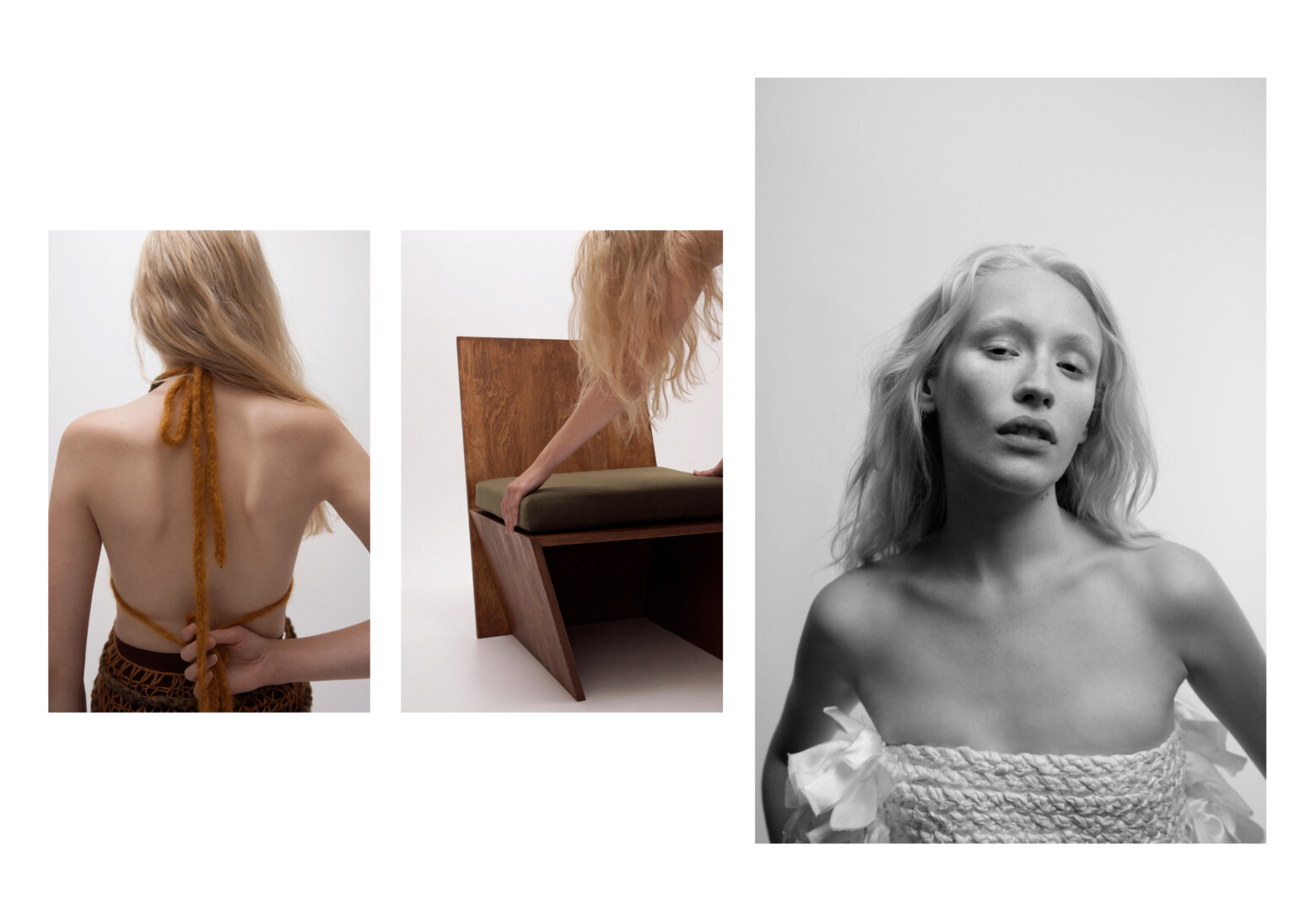

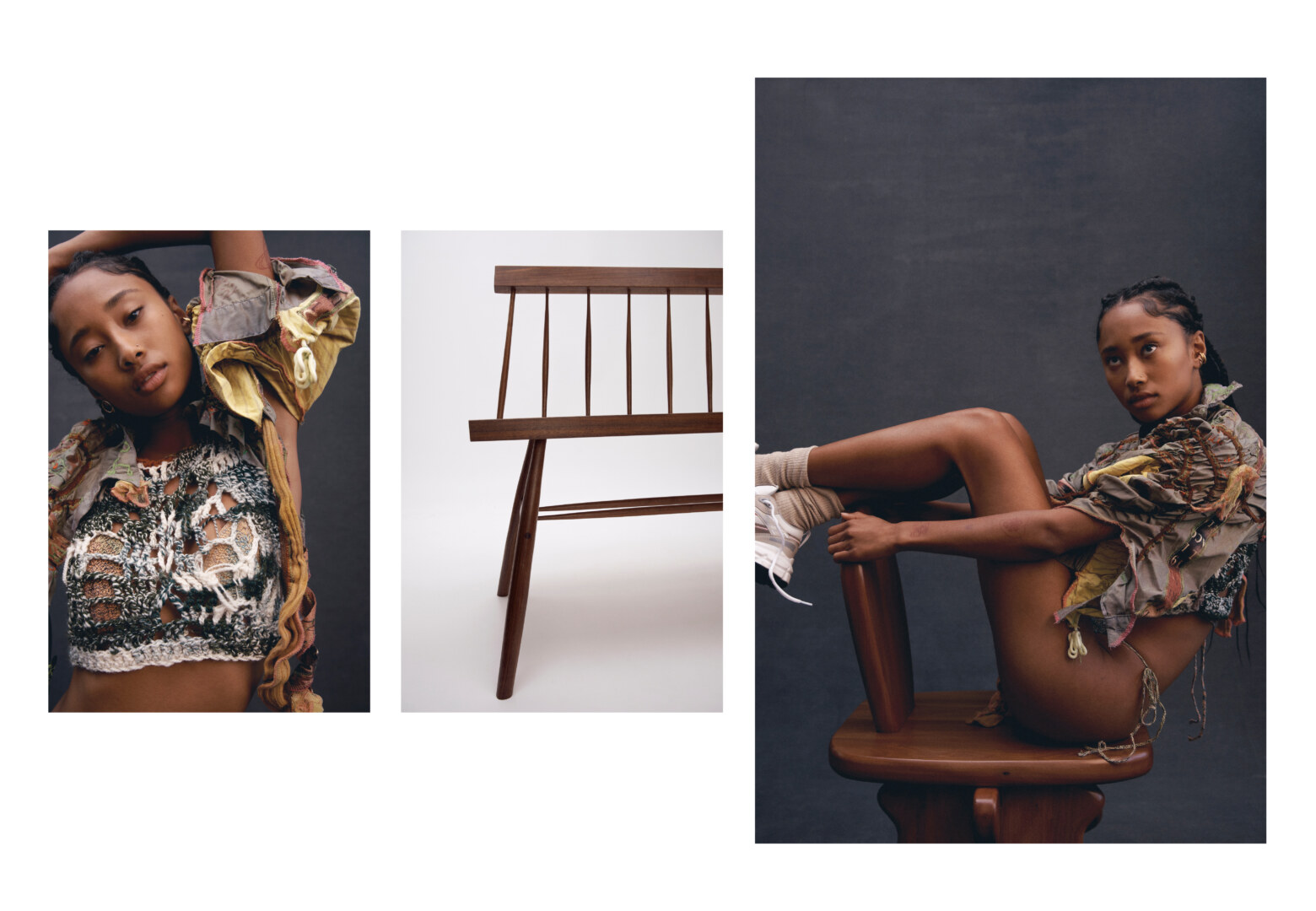

Youkhana dress, Livio Tobler chair

BY HAND BY KELLY GEDDES AND MARIELA SUMMERHAYS

PHOTOGRAPHER: Kelly Geddes @ Saunders and Co Agency

PHOTOGRAPHER'S ASSISTANT: Hamish McIntosh

ASSISTANT: Conrad Wainwright

ART DIRECTOR: Karla Clarke

STYLIST: Nichhia Wippell

MAKEUP: Teneille Sorgiovanni @ After Winter Agency

HAIR: Georgia Ramman

POST PRODUCTION ARTIST: Rebekka Johnson

MODELS: Kristina Byerley and Eyes @ Priscillas, Tiama @ IMG

WORDS: Mariela Summerhays

DESIGNER: Francesca Nwokeocha

As creatives, there is an awareness that what we write, design and photograph, may hold you for a moment, satiate your curiosity, before you desire again. It’s why so many words litter the internet; why so many closets purge and gain clothing every season without fail. However there is only so much we can consume before it consumes us, and we crave for the satisfaction of hand moving yarn across, in and around itself; before we wish for elbow driving forward circular saw, and the confirmation of progress by sawdust in the air. Driven by this dormant urge, there are those who are reclaiming the old way of craftsmanship, and finding pleasure in the act of slow and meditative methods of creating art.

As building by hand moves beyond conscious thought and enters routine processes, it has been observed by psychologists that spontaneous and creative ideation is able to occur. Such was the case for Annalisa Ferraris, a longtime painter-turned-furniture and fittings designer.“I have been painting for about a decade,” she explains. “And in the past couple of years, I’ve felt a bit agitated doing just the one thing creatively.” In her search for another creative outlet, Ferraris found paravents — or, folding screens — her first foray into three-dimensional and functional craft making. “I felt so excited again, and I think when that happens it can become like a flood gate,”she enthuses. “All of a sudden I was thinking, ‘What else can I design? Where else could this stretch?’ And I saw my panel painting as a golden brass sconce; I imagined the furniture inside the places I’d painted, and the lives that surround them.”

In this story by Kelly Geddes, Nichhia Wippell and Karla Clarke, Ferraris’ birch plywood occasional chair sits in the centre of frame, its hard lines and simple form reflective of the Art Deco era that informs her artist practice; “Much like the era itself— the ‘20s and ‘30s were all about the joie de vivré, indulgence and luxury — I wanted my furniture to have the luxurious aesthetic and simple sophistication that was so prevalent at that time.” Should curious observers peek at Ferraris’ socials, they’d find images of Paravent I, her shadow-informed folding screen that started this expansion of creativity; and Paola, the brass sconce she imagined so vividly, then sculpted into reality. “You’re thinking about something people are going to be physically interacting with, as well as visually or emotionally. So you’re shifting plains— which is more exciting than I had anticipated,” Ferraris shares of her newfound love of sculptural work. “There’s still so many ideas I’m working on, it’s really just the beginning, and that’s an incredibly exciting place to be!”

Platonic Lover knitwear top, Annalisa Ferraris chair

Platonic Lover knitwear top, Annalisa Ferraris chair | Youkhana dress

Caroline Reznik sweater, Lott Studio earring, Ryan Storer ear cuff, Livio Tobler chair

Caroline Reznik sweater, Lott Studio earring (right ear), Ryan Storer ear cuff (left ear) | Redrew Clothing dress, Caroline Renzik bodysuit

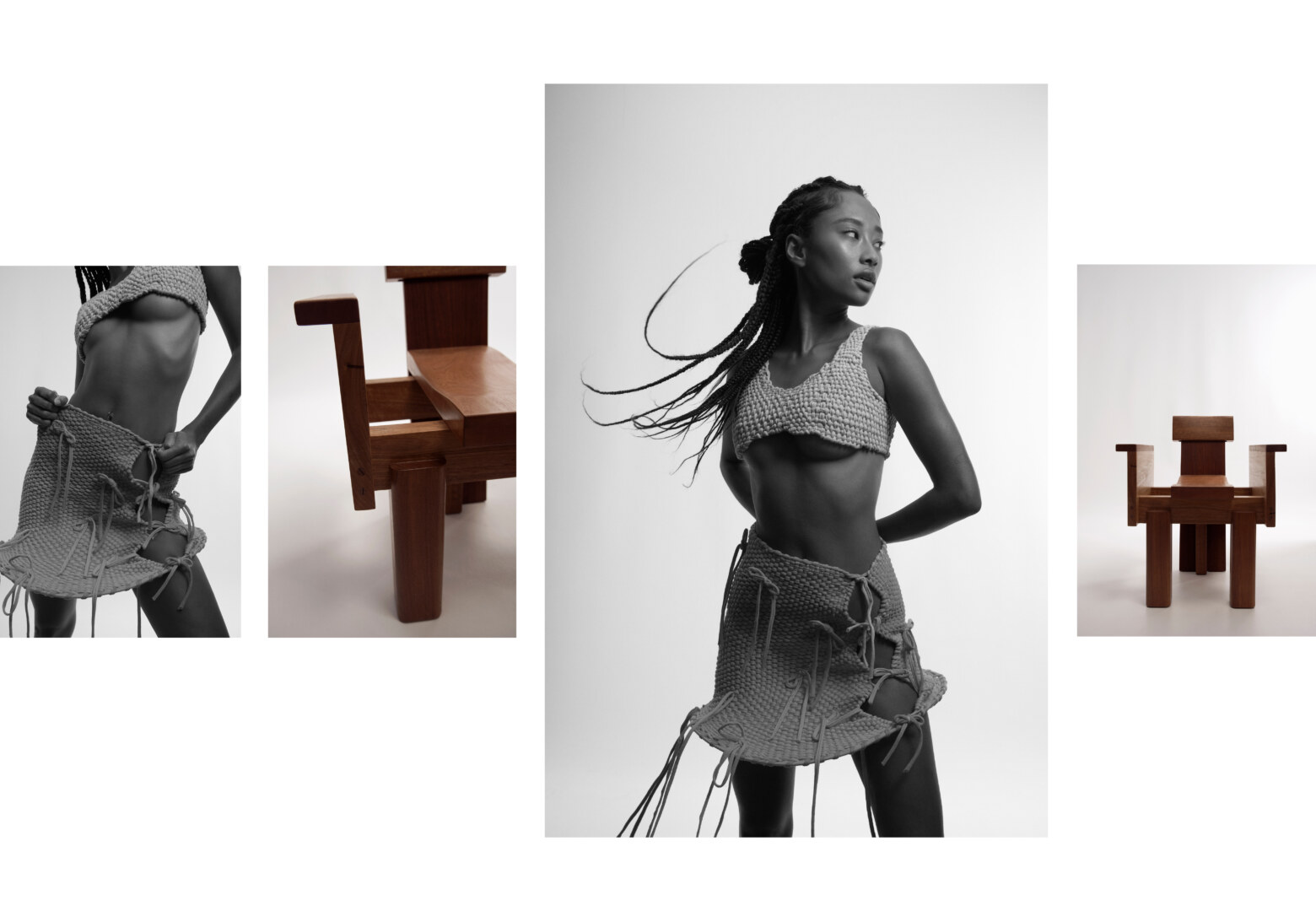

Xi Wu Studio top

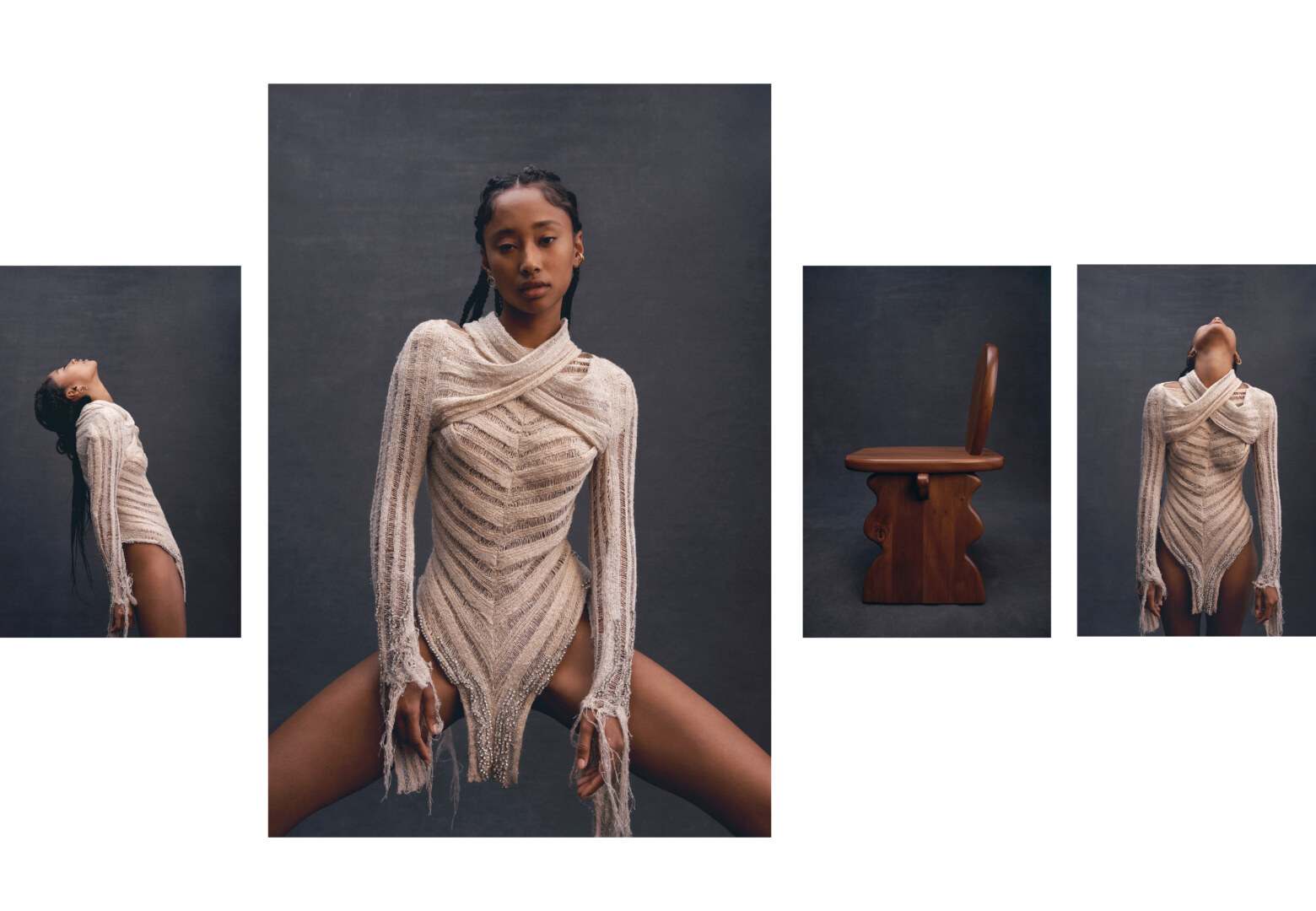

It is natural that our subconscious imaginings and moments of spontaneous creativity often bring us back to childhood, and to our heritage and cultural identity. Combining his expertise from prior occupations in graphic design and construction, furniture designer Livio Tobler’s work elicits an immediate visceral response in viewers, the use of salvaged timber and stone married with the sentimental inspirations that inform their construction. “My inspirations, like most, are drawn from childhood memories, upbringings and new encounters,” Tobler shares. In images for this story, fluid, expressive lines meet the solidity of wood, locking together in a chair that is playful form and absolute function in one. Another, like a child’s building blocks, is joyfully pieced together. “Some of [my inspirations] would be from the ornamental facades and interiors of traditional Swiss alpine houses where I spent time growing up — and where my mother now lives — as well as the contrasting contemporary architecture that Switzerland also has.”

Captured elsewhere in this shoot, a laser cut perspex vest hangs loosely from a model’s frame, catching the light with her every movement. In an interrogation of bicultural identity and its designer’s heritage, Xi Wu Studio’s garments starkly contrast modern technologies — such as laser cutting and technical materials — with the craftsmanship of traditional fabrications and techniques, such as quilting. “My aim was to merge two motifs that contrast in their tradition and significance to celebrate the relationship between the old and new,” designer Xizhu Wu explains of this deeply personal work. Houndstooth, a Scottish heritage textile usually woven into wool, is intertwined with ‘FU’ 福, a character symbolising good fortune, blessing and happiness; “It is an indispensable decoration item for every Chinese household, especially during the Chinese New Year.” Lastly, jade beads embellish the fabrication, a propitious stone that signifies good luck, hope and fortune in Chinese culture.

“Just as my end pieces represent the unique intersection of my cultures, I believe the processes and techniques required to produce the very materials need to be just as special,” Wu says of the detail-oriented and meaning-laden fabric of her own creation. It simply isn’t possible to achieve the depth of contemplation her work inspires with textiles purchased at whim from the local haberdashery. “Unique and new identities are created from the merging of cultures — through the creation of composite materials, I’m creating garments that hold so much story for those that can delve deeper than what’s on the surface.”

Xi Wu Studio top

Livio Tobler chair, Lilli Mckenzie skirt

Lilli Mckenzie skirt and top, Livio Tobler chair

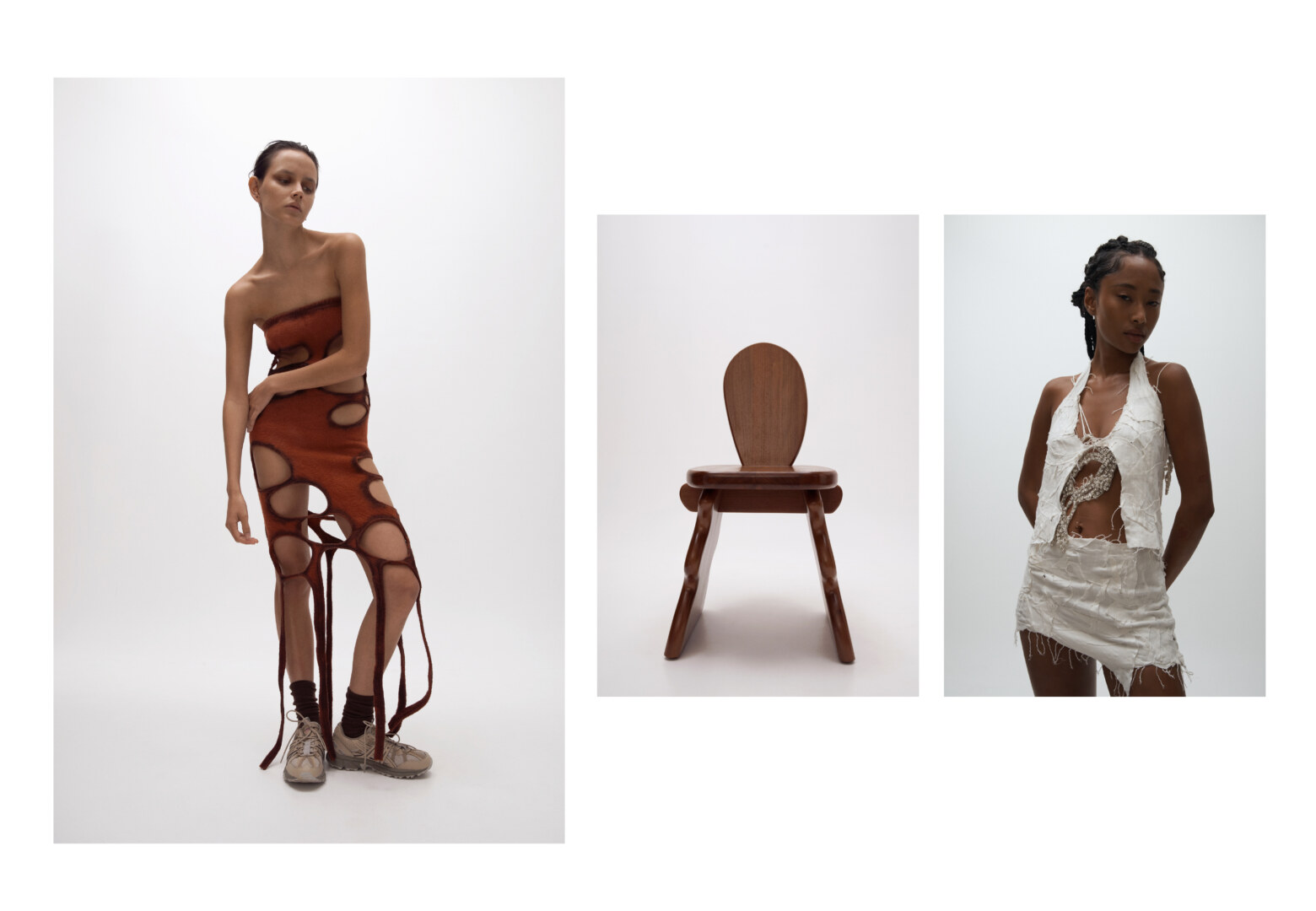

Livio Tober chair | Terminal Six dress

Terminal Six dress | Livio Tobler chair | Pach Project top and skirt, Caroline Reznik top and skirt

Youkhana bra and dress | Pach Project top, Jodie mittens

Platonic Lover knitwear top

Creating by hand has the distinct joy of unadulterated self-expression, yes; but for some, it also presents an opportunity to act as a conduit between how people truly are, and how they present themselves to the rest of the world. Youkhana’s distinctive, braided garments’ beauty is in the consideration that is given to the individual who comes to wear them. Visually immersive through colours, emotionally evocative through shapes — but ultimately, in service of the uniqueness that belongs to each person. “I find creating and having collaborative relationships a very fun and exciting process. It feels special and personable,” designer Nathaniel Youkhana shares. In still images here, his signature braids circle neck and hips, the dandelion yellow of the fabrication both energising and soul-nourishing. “There’s always a hint of them and a hint of me in the piece. I’ll start making something with someone in mind; or a colour will resonate with me, and we work to reflect their personality and who they are as a person in that garment.”

Platonic Lover Knitwear’s philosophy is likewise grounded in the connection between people, its knitwear inspired by those Daisy Barrow Piper loves (“I seem to have these intense connections with the people who are closest to me,” she confides. “So it goes without saying that this is where I draw most of my inspiration from”), and is intended to be worn whichever way the wearer pleases. In this way, any stranger becomes a collaborator with Barrow Piper. “I wanted to put emphasis on the body as a figure that can be embellished in multiple ways,” she explains. “With each one, a different silhouette is created.” Here, a model wears a densely knitted top layered over a mesh dress, her arms intertwined with another’s, who is adorned in a top that could be a skirt (that on some, could also be worn as a dress). “The possibilities that the garment takes on is dependent on how the wearer or viewer wishes to express themself, and how they feel on any given day.”

Australians will immediately recognise the label’s colour palette as one we’re blessed to know intimately; rusts, ochres, dove greys and sage greens that make every office worker long for the weekend, when we can return to the rainforest or seashore. “If I am not in the studio, I spend a lot of time by the ocean, laying on rocks,” Barrow Piper says. “I am constantly attempting to work the tones and colours of the seascape into the knitwear, it just makes the most sense.” Barrow Piper observes how the time spent with each lovingly created piece turns the garment into an extension of herself, so intimate and repetitive a motion it is to knit a single strand of yarn into fabric. I’m reminded of a favourite fairytale from childhood, The Wild Swans by Hans Christian Andersen, in which a princess painstakingly knits shirts out of love for her brothers, day after day in a forest, to release them from a spell that has turned them into swans.

Livio Tobler chair, Rutt bag | [left] Platonic Lover top, dress and skirt, [right] Platonic Lover top and Indrahas dress

Livio Tobler chair | Indrahas dress and bikini

Ted O'Donnell chair, Youkhana bra and dress

Ted O’Donnell is the most recent to heed the call of the tactile, after a previous lifetime as a photographer. Roses caught in the height of their bloom, submerged in water and intertwined with coloured ink; the photography series he pursued for a decade — in collaboration with his creative and life partner, Vicki Lee — captures the ephemeral, that which is fleeting. But comfort zones are the enemy of creativity, and the project reached its natural conclusion last year, culminating in an art book — a sign, perhaps, of a more slow, handcrafted occupation to come. Nestled among this story’s photographs, a model reclines against his American walnut bench, fumed to bring out the richness of the wood’s colour. As all his pieces, the bench has been made entirely without power tools, its parts split with axe or frow, its elegant spindles shaved with drawknives and spokeshaves. “Instantly, I was drawn to this path of deep understanding, and the slow path to mastery,” O’Donnell says of Japanese woodworking tools, which rely on the sensitivity and skill of the craftsman to bring wood to its final form (unlike power tools, which are, in part, designed for immediate gratification). “I now use only hand tools for every part of my woodworking.”

Upon first working with wood, O’Donnell says, “something in [him] switched” and he had to honour the call. “It’s not an uncommon experience,” he asserts, of the feeling of recognition one feels upon creating with our hands. It is perhaps the underlying reason why in film, literature and history, he who creates by code and pixels is often cast as the villain; Jesse Eisenberg staring unfeelingly at a wronged Andrew Garfield as he tears Facebook’s headquarters apart, after learning of the ways he’s been deceived. A carpenter’s son, Jesus, however, moves the hearts of all who hears him; and centuries later, The Notebook’s Allie ultimately chooses Noah, the man who builds her dream home without certain hope of her ever living in it with him. It belongs to all humans, this dormant urge to feel our way through creativity with only hearts and hands. “There is a strong physical response — something buried in our DNA, I believe — that understands the material, and senses what is possible.”

Jodie dress, Livio Tobler chair

Jodie top, Terminal Six jacket, Ryan Storer ear cuff | Ted O'Donnell chair | Livio Tobler chair

Caroline Reznik headpiece and jacket

_________

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.