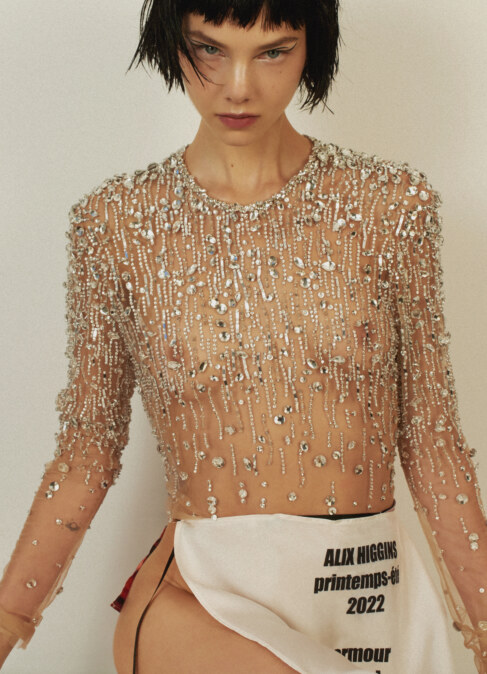

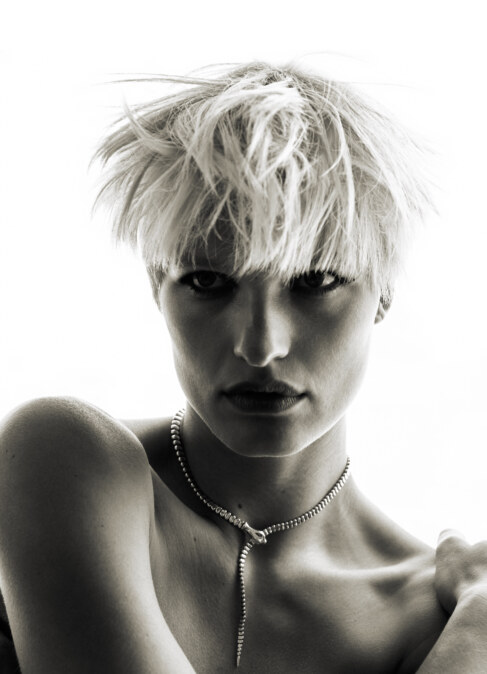

BODY TALK BY MANOLO CAMPION AND MARIELA SUMMERHAYS

PHOTOGRAPHER: Manolo Campion

1ST ASSISTANT: Nick Garcia

DIGI: Arlo Pyne

MOTION: Stella Sciberras

STYLIST: Emma Kalfus

HAIR: Taylor James Redman

MAKEUP: Filomena Natoli @ viviens

MODEL: Anisha Sandhu @ merci management & Ambar Cristal @ chic

WORDS: Mariela Summerhays

DESIGNER: Francesca Nwokeocha

An 1879 oil painting by Édouard Manet, Chez le Père Lathuille, is perhaps one of the most famous portrayals of attraction, restrained interaction between a couple though it may be. Bodies turning towards each other at a restaurant table for two — ignorant to the proprietor’s enquiring look over their shoulders — the man holds the back of the woman’s chair and her gaze at once. It is evident desire has moved into attraction. Words spoken to express our desire or attraction to each other can all too often sound alike; our bodies, however, will tell us all too clearly the difference.

To commemorate Valentine’s Day in 2017, Harvard University published a paper that illuminated the science behind the effects attraction has on our body. Similar but distinct from desire — which can be experienced simultaneously, but likewise without — attraction is not the meeting of eyes from across the room, but that intoxicating phenomenon after, when two have moved towards each other and find pleasure in each other’s presence.

Celine jacket, Elizabeth K. stockings, stylist own vintage knicker, Bottega Veneta earrings

[left] Prada top (worn underneath) | Speed tank top | Beare Park skirt | Miu Miu sandals | [right] Valentino blazer, bodysuit, gloves and tights

Prada leather jacket and skirt

Unlike the primary hormones, testosterone and oestrogen, stimulated by the hypothalamus — that most vital region of the brain that controls our emotions — during initial desire, the stages of attraction are marked by the release of dopamine and norepinephrine. “These chemicals make us giddy, energetic, and euphoric, even leading to decreased appetite and insomnia — which means you can actually be so ‘in love’ that you can’t eat and can’t sleep,” author Katherine Wu wrote. In Manet’s painting, there is nothing but a glass of champagne and bread on the table; a scene recreated every weekend by couples in the first flush of attraction even now.

Hatred — pure, white hot hatred — often makes itself known in the sudden colouring of someone’s cheeks, neck and ears, where blood has rushed to all at once. This can be attributed to Hatred’s steadfast companion, Anger, who will drastically increase blood pressure and quicken once-resting heart rates. In a most painful scene of Noah Baumbach’s 2019 film Marriage Story, a heartrending portrayal of divorce, Scarlett Johannson and Adam Driver’s calm exchange devolves into a horrific verbal altercation, their faces and neck flushed red with emotion. “They don’t know where to put all of this pain, so they put it into this language, these physical gestures,” Baumbach said later of the scene.

[left] Saint Laurent dress, Dinosaur Designs Louise Olsen earrings | [right] Miu Miu top and sandals, Reborne Store vintage skirt

[left] Miu Miu top, vintage lace bodysuit (worn underneath) from Reborne Store, Balenciaga boot, Valentino shorts | [right] Miu Miu top, skirt, belt, and sandals

Levels of adrenaline and cortisol — the stress hormone — increase with an active participation in hatred, and are most commonly associated with the ‘fight or flight’ response; an acute stress response triggered by encountering a perceived threat. It is likely in this agitated state that poor decisions are made; that you would say or do things that would never be inspired by amorous or neutrally-perceived company. As the former couple exchanges barbed words aimed to maim, hitting where it hurts most, Driver’s character punches a hole in his apartment’s wall; the visual allegory of a broken home. More than enemies, it’s the person who was supposed to love us, but kept us from the realisation of ourselves that we hate most.

Love, unlike attraction and hatred, is not as easily discerned by physical cues. Produced by the hypothalamus and released in large quantities during sex, breastfeeding, and childbirth, oxytocin creates a deep emotional connection with those for whom we already have an affection for, and is the best explanation physiology gives us for the presence of love. As attraction grows and wanes throughout a shared life, oxytocin reaffirms our commitment to each other. However, without obvious outward physical signs to indicate levels of the hormone, we stumble through gestures, and confuse the signs of attraction for attachment. For this reason, there is perhaps no other experience we desire verbally articulated more than love; even more so when we believe that love has possibly turned to hate.

Ulay’s surprise appearance at Marina Abramović’s performance at the Musuem of Modern Art in New York, The Artist is Present, illuminates without words whether love can still exist where there has been hatred. It took place more than twenty years after the former lovers and artistic collaborators’ final farewell — an appropriately epic work of performance art that saw them traverse the Great Wall of China from either end, meeting in the middle only to say goodbye.

Valentino blazer, bodysuit, gloves and tights | Bottega Veneta shoes

[left] vintage dress from Reborne Store, and Miu Miu top (around waist) | [right] Dinosaur Designs necklace | Sundessi gloves

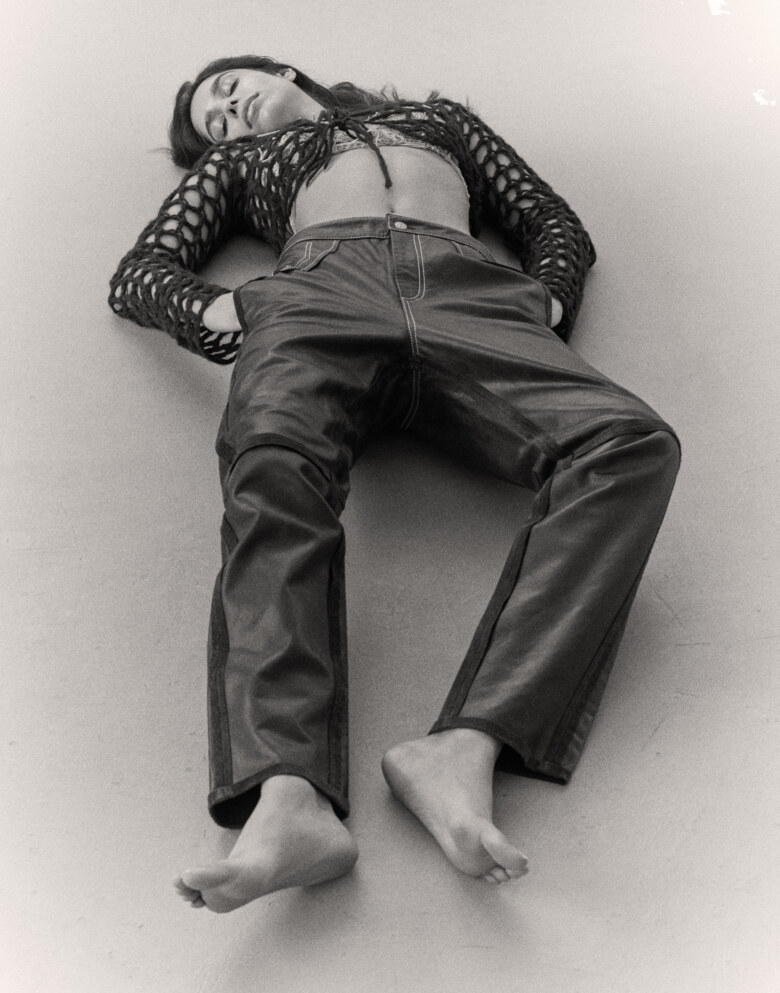

Sundessi bralette and cardigan, Maison Margiela leather pants from The Turn

“For her, it was very difficult to go on alone. For me, it was actually unthinkable to go on alone,” Ulay described of their deteriorated 12-year romantic and collaborative relationship. “If love is broken it turns to hate. She hated me.”

However — for eight hours a day, over a period of two and a half months — Abramović was seated silently at a table, with only a single empty seat opposite. Members of the public were invited to fill the seat, for moments, minutes, even hours, across from her, and both participant and artist simply held the other’s presence. Then Abramović would close her eyes as participants moved on, and another moved in, preparing herself for the transfer of energy with whomever was next. That first night, when she opened her eyes, that someone next was Ulay.

Wordlessly smiling at each other — as tears filled Abramović’s eyes, and after a wistful shake of Ulay’s head — Abramović reached for Ulay, breaking her own performance piece’s non-contact rule. It is here where physiological explanations of love break down, because after two decades, there had been no reaffirmation of attachment; no release of oxytocin after nights going to bed with each other, and being there in the morning when each woke. Still, as surely as attraction being a hand resting on the back of another’s chair, and hatred being the crumpling of drywall under your fist; love must be the extending of hands across a table to clutch another’s.

_________

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.